Knopf published only one issue, or volume, of the Knopf Short Story Sampler, offering for Spring 1996 four stories and a set of vignettes from five upcoming collections from five different writers, and crediting no editor. No previous publication indicators, either, so I'm not sure which might've appeared previously in The Atlantic or The Fiddlehead or Antioch Review (I've been able to track a few online, including one from Antioch, as it happens). A loss-leader of a promotional item, its circulation was limited by design...I ended up with the copy sent along to our bookstore, as I doubt anyone else was much interested. I suspect that it didn't, nationally, do as much to draw attention to the five new collections as was hoped. Also, no one has an image online that I can find of its handsome if functional cover, so I will eventually put one up.

Knopf published only one issue, or volume, of the Knopf Short Story Sampler, offering for Spring 1996 four stories and a set of vignettes from five upcoming collections from five different writers, and crediting no editor. No previous publication indicators, either, so I'm not sure which might've appeared previously in The Atlantic or The Fiddlehead or Antioch Review (I've been able to track a few online, including one from Antioch, as it happens). A loss-leader of a promotional item, its circulation was limited by design...I ended up with the copy sent along to our bookstore, as I doubt anyone else was much interested. I suspect that it didn't, nationally, do as much to draw attention to the five new collections as was hoped. Also, no one has an image online that I can find of its handsome if functional cover, so I will eventually put one up. Contents:

5 * Interference * Julian Barnes * The New Yorker, 19 September 1994; Cross Channel (Knopf 1996)

25 * [group of linked, at least by implication, vignettes] * Diane Williams * The Stupefaction (Knopf 1996)

25 * An Opening Chat

27 * The Key to Happiness

29 * A Shrewd and Cunning Authority *Antioch Review, Spring 1993

31 * The Everlasting Sippers * Iowa Review, Spring/Summer 1994

33 * The Power of Performance

35 * The Blessing

37 * Eero

41 * Papantla * Sam Shepard * Cruising Paradise (Knopf 1996)(story first published 1990?)

53 * The Enchantment * Christine Schutt * Nightwork (Knopf 1996)

67 * Batting Against Castro * Jim Shepard * The Paris Review, Summer 1993; Batting Against Castro (Knopf 1996)

What's interesting to me, at least, about this assembly is the relative similarity of the (somewhat more famous) men's stories, as contrasted with (the certainly not unknown, but not as well-known then nor now) women's, which are also similar (and Williams and Schutt have since worked on the annual magazine Noon together). The Barnes concerns an English composer in the early 1930s on his lingering-deathbed, in a house at the outskirts of a French village, where he lives with his too-indulgent former-singer life partner, she having given up on her budding career to be Wife in all but legal recognition some decades previously, as he's going into his final spiral and using that as a means of keeping a grip on her life and of those around them as much as possible, while still hoping to get her to appreciate his Intended Last Gift to her, a thematic piece of music she hasn't been impressed with, newly recorded and featured on a BBC longwave broadcast they can barely pick up.

The two Shepards (not related as far as I know, and Shepard was actually the late Sam's middle name) also provide stories of men in other countries, Americans in their cases in a fairly recent adventure in on-location filming in Mexico ("Papantla") and early/mid-1950s winter baseball in the Cuban National League for three marginal Big-League baseball players trying to improve their records or physiques for the next US season. While the Williams is (or at least seems as presented) a series of prose snapshots of a woman undergoing institutionalization after somewhat unspecified breakdown, albeit with a sexual component and a more or less growing sense of dissociation as one passes from one vignette to the next (though these vignettes were published in different venues originally, rather than grouped), and the Schutt story is a very allusive account of the events leading up to a violent attack of a young adult daughter on her father, who had been an erratic creature all his life, married three times and conducting an incestuous relation with his daughter in her childhood before she is relocated to live with her grandparents.

So, the exoticism of the men's stories is mostly in their setting, and about Anglophone men to one degree or another trying (ultimately fruitlessly and never with any true benefit) to impose their will and/or understanding on people in, for them, fairly exotic circumstances, and the women's stories are about extreme reactions to horrible everyday existences among those raised in comfortable domestic US surroundings made terribly unpleasant.

What this says about the editorial decisions being made at Knopf about what short story collections they chose to publish, and what to highlight in them for promotion, in 1996, isn't too surprising, though, again, interesting in its lack of novelty, and all the work is well-written, at very least good of its kind. As the bromide instruction for all anthologists is to put your strongest stories first and last, it probably isn't accidental the Barnes leads and the Shepard baseball story bats cleanup. They all seem much of their time, in the contemporary/mimetic publishing scene of two decades ago, even given that the Schutt is also crime fiction and the Jim Shepard is unabashedly historical sports fiction (some knowledge of baseball will help in understanding the references)...and of the current scene as well, though perhaps there'd be more fantasy in such a collection released today, as there also would've been twenty years before.

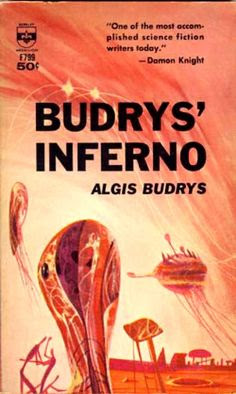

As Ed noted in his obituary for Budrys linked to above, they were colleagues not only as writers who were artists but also as workers in the advertising and public relations industries, when he conducted his interview with Budrys in 1977 in Dubuque, not too far from Ed's home in Cedar Rapids and Budrys in town to lecture George R. R. Martin's college writing workshop class. It's a fine interview, digging somewhat deeper in some ways at least than did Charles Platt's interview for Dream Makers (Ed had more space to play with, at least in the finished product), and Ed notes in the introduction to the interview that Budrys had a reputation for being Difficult and Brooding, which inspired Budrys to write the essay, cited on the cover above, to follow the interview in this issue, "On Being a Bit of a Legend"...which is about how he interacts with those around him who choose to be importunate or worse as well as those who are consistently polite, and how he will step back inside himself and reconsider others when they seem to profoundly misunderstand him or his work. Budrys notes that his seeming

As Ed noted in his obituary for Budrys linked to above, they were colleagues not only as writers who were artists but also as workers in the advertising and public relations industries, when he conducted his interview with Budrys in 1977 in Dubuque, not too far from Ed's home in Cedar Rapids and Budrys in town to lecture George R. R. Martin's college writing workshop class. It's a fine interview, digging somewhat deeper in some ways at least than did Charles Platt's interview for Dream Makers (Ed had more space to play with, at least in the finished product), and Ed notes in the introduction to the interview that Budrys had a reputation for being Difficult and Brooding, which inspired Budrys to write the essay, cited on the cover above, to follow the interview in this issue, "On Being a Bit of a Legend"...which is about how he interacts with those around him who choose to be importunate or worse as well as those who are consistently polite, and how he will step back inside himself and reconsider others when they seem to profoundly misunderstand him or his work. Budrys notes that his seeming awkwardness in some stressful social situations is as a result of just this sort of reassessment kicking into gear, particularly when others make a point of underestimating him to his face. This certainly resonated with me, as one who like Budrys spent a good part of my youth being bullied and chivvied by those around me, and found that often I was underestimated in several ways by adults as well as fellow children when young, as I would be by colleagues and bosses later in life. Meanwhile, Ed's questions about his adventures in PR lead to a rather charming long anecdote about a publicity stunt in Chicago, near the site of the Picasso stature, where Budrys and some confederates briefly displayed a 12-foot plastic statue of a wet pickle on behalf of Pickle Packers International, a trade organization. (In one of Budrys's most powerful essays, written initially as a book-review column for Galaxy magazine and collected in Benchmarks: Galaxy Bookshelf [and the 30th anniversary anthology devoted to Galaxy], he describes in detail his experiences while working east

coast news desks for the Packers and finding his way back home to the Chicago suburbs during the riots and other aftermath of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr....and how that related to sf, the deep-seated desire for power-fantasies inherent in much of the worst and some good and certainly popular sf, and what that augured for the future of us all.) And Ed noted that among his favorite of Budrys's then recent columns in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction was his explication of H. P. Lovecraft, whose work Ed had been unable to enjoy before reading Budrys's take on how the man's life informed his work. There are preliminary plans to get issues of Science Fiction Review archived online, though there has been a bit of foot-dragging, given how massive most issues are and how many contributors were willing to put things bluntly and without filter, whether about beefs with publishers or other writers, or their view of the world.

Another writer, one who had a somewhat more intimate view of H. P. Lovecraft, of course, was Fritz Leiber, who began corresponding with Lovecraft after Jonquil Leiber, Fritz's wife, wrote to HPL via Astounding Stories magazine to note how much she and her husband enjoyed Lovecraft's fiction, and that her husband was an aspiring writer himself (while working mostly as an actor with his parents'company and other gigs). As Leiber writes in an essay for Marion Zimmer Bradley's Fantasy Magazine, published a couple of years before his death, in tandem with a Darrell Schweitzer interview conducted before an audience at the 1990 Philcon (the annual Philadelphia sf/fantasy/horror and related matter convention which these years happens about a mile away from my current residence). In the essay, Leiber discusses how and how much Lovecraft made a difference in his early literary career, and how Leiber and his old friend Harry Otto Fischer devised the characters Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser based on themselves, in part with the intent of writing independently about them, and how Leiber tried briefly to nudge their first collaborative story, "Adept's Gambit", in a more explicitly Lovecraftian direction. Despite also corresponding with Lovecraft, Fischer was against this and Fischer prevailed, even when the novella was first published in a collection of Leiber fiction from Arkham House, August Derleth's imprint founded mostly to preserve Lovecraft's legacy. In the interview, Leiber goes on to describe his development as a writer both during his year of correspondence with Lovecraft before HPL's early death, and his subsequent work, ranging from early office jobs writing pop science (he was, as is not mentioned here, later for some years an editor at Science Digest magazine) and early fiction career publishing in John W. Campbell's magazines Unknown Fantasy Fiction and Astounding Science Fiction till the first folded during World War II, and Campbell in the late '50s took umbrage at Leiber for selling a story with the same basic setting to Galaxy at the same time as a completely different but linked story to Astounding. (Both Budrys and Leiber, here and elsewhere, are very open about their debts to Campbell as editor, and very willing to point out his flaws .)

That I choose to link these Budrys and Leiber items, published fifteen years apart, might be seen as stretching the points, despite the effect both writers have had on my ways of thinking about life and, of course, fantastic fiction (when Budrys was conducting his column in F&SF, Leiber was the books columnist in Fantastic, for further small parallel, though theirs were among the critical writing I read most eagerly)...I had just pulled them out of storage boxes, along with Knopf item, over the course of the last couple of days. They are worth finding, or revisiting, if you are, as I am, lucky enough to have copies at hand for perusal. Digging into the works of all the writers dealt with in this little review could be worth your effort...none of them are trifling with their art, and all are swinging for the fences.

For today's other books and book-analogs, please see Patti Abbott's blog.

4 comments:

I've read many of Algis Budrys's reviews. Terrific insights! And, you can't go wrong with Fritz Leiber!

At his best, no one was doing better literary criticism in fantastic and "thriller" fiction (the latter mostly for the CHICAGO DAILY NEWS) than Budrys, and his fiction was often brilliant, if too sparse over his career.

Leiber was a brilliant critic when he chose to be as well, as well as an even more brilliant fiction writer at his best.

George, I imagine you've read Barnes and Sam Shepard, at least, and I know you've read some of Ed and Darrell's work...

Thanks as always Todd, not last for turning my memory back to Lovecraft, an author I have struggled with and gave up on a while ago - not just for his somewhat dense style but also for his more 'reactionary' views (and I think I'm being pretty polite). What you say about Budrys and his view on those who came to speak to him is fascinating though - cheers mate :)

Yes, there's a lot to dislike about Lovecraft's work, and I've rarely been too fond of his intentional fustian and attempts at heightened language to get across the existential terror of his vision...his immediate predecessors and most of his colleagues not drawn to Farnsworth Wright's years at WEIRD TALES tended to write as clearly and elegantly as they could, but Wright had a love for affectation of prose that could exceed, by intent or ineptitude, the worst purple Poe or the Decadents might have offered in the previous century. So, while he published Algernon Blackwood, and Clark Ashton Smith who had a surer hand with this kind of prose, Wright certainly encouraged Lovecraft's desire to be at times as discursive as a windier version of an 18th Century essayist, and that of such Little Lovecrafts as Frank Belknap Long or the very early work of Robert Bloch. And then there was HPL's juvenile and extended embrace of some of the worst chauvinism of his day...he was showing some signs of getting past at least his anti-Jewish idiocy by his brief early middle age, having had a short but amiable marriage with Sonia Greene and mentoring Bloch particularly while also serving the same function for Leiber, Greene and Bloch both being Jewish. We can hope he would've continued to Wise Up, had he lived. Lovecraft's vision of existential horror is most of what is valuable in his work, and it certainly, as I'm wont to note, had a Very profound effect on Bloch and Leiber both, as they found their feet as writers and began exploring so influentially the implications of that vision as they saw it themselves...and they were both, line by line, far better prose artists than Lovecraft.

You can do much worse than to read Ed's interview and the Budrys essay...perhaps I should get more directly involved in making it more accessible. Or no perhaps about it.

Post a Comment