It's a magazine, and it's a hardcover...the latter has better paper, but the same typesetting; the covers are comparably uninspiring. Dell, parent company of the Dial Press, all just purchased in 1976 by Doubleday, continues its long history of being in the Hitchcock book business...before eventually purchasing Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine and its fiction-magazine stablemates from the then-collapsing Davis Publications in the early 1990s. The Dial hardcovers were mostly aimed at the library market, though Doubleday's relatively cheap production methods meant the hardcovers weren't the most durable of volumes--the glued (rather than sewn) first signature of my copy, having already been creased severely by some previous reader (this wasn't a discard, but I did pick it up at a library sale) broke away from the binding as I rather carefully read it...I suspect the magazine form would be hardier.

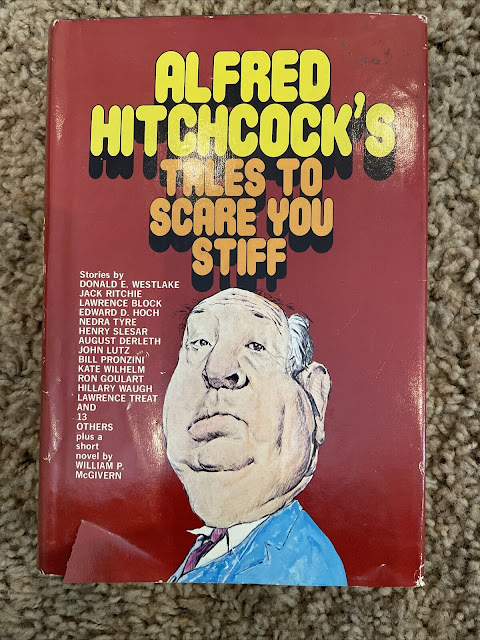

This issue was also available in hardcover (Dial 1978 as Alfred Hitchcock’s Tales to Scare You Stiff). In the Beginning, or at least in 1945, Dell Books begat the first anthology attributed to then-young-middle-aged film director Alfred Hitchcock, in the Dell MapBack paperback series, Suspense Stories. This also began Dell's rather devious (but hardly unique) practice of obscuring the actual editor of the Hitchcock (or other famous person) volumes, who in this case was probably Dell's own Don Ward, who edited most of the early Dell "Hitchcock" paperbacks, as well as the Dell magazine Zane Grey's Western Magazine (which ran from 1946 to 1954, and which got better and better the less Grey fiction it reprinted). In 1956, HSD Publications was formed to publish Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine, not at all coincidentally with Alfred Hitchcock Presents: beginning its television career in Fall 1955. Likewise, by 1957, Random House engaged fiction and script-writer and magazine editor Robert Arthur to ghost-edit a series of anthologies also entitled Alfred Hitchcock Presents: [various usually darkly humorous subtitles]; by 1961, these were joined by a young readers' series, with the first volume, Alfred Hitchcock's Haunted Houseful, ghost-edited by YA specialist Muriel Fuller, but subsequent volumes, till his death in 1969, edited along with the adult-AHP: series by Arthur. (Arthur was also called to upon to devise a Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew-style series devoted to Hitchcock and the youthful The Three Investigators, and he wrote the first several volumes and edited the series initially afterward.) Other tv-driven projects included the 1957 Simon & Schuster anthology Stories They Wouldn't Let Me Do on TV, possibly assembled by Arthur but definitely by the network and/or sponsor censors via refusal (and in reprint editions, often intentionally retitled "AH Presents: Stories...") and writer Henry Slesar's first collection, an Avon Books paperback A Bouquet of Clean Crimes and Neat Murders; Slesar had contributed scripts and source stories to the AHP: tv series and Hitchcock branding was much in evidence. Meanwhile, Dell was very much interested in keeping their hand in, by reprinting the older anthologies they had originated and from others, publishing paperback editions of the Random House adult books that mostly split the hardcover contents into two softcover volumes, and, in the early '60s, beginning to publish best-of volumes from AH's Mystery Magazine...all packaged as if Hitchcock was the editor, and all looking rather like one another, whatever their content's source. In the UK in the latter '60s, busy editor Peter Haining would also begin editing "Hitchcock" anthologies, mostly not seen in the US (though Dell would publish the last one, in 1971) for Four Square, then New English Library. HSD would publish the magazine till 1976, selling it in late '75 to Davis Publications, formed in the late '50s when B. G. Davis left Ziff-Davis in part because the house he co-founded was less and less interested in publishing fiction magazines; Davis started his second firm with the purchase of Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine from Mercury Press, and one of Davis's innovations was to begin publishing as well a reprint magazine called Ellery Queen's Anthology drawing mostly from the back pages of EQMM...by late '76, under B. G.'s son Joel Davis's direction, Alfred Hitchcock's Anthology magazine had joined the stable...and the Dial Press hardcover editions came with them. Davis Publications, having suffered an expensive failure in launching a Sylvia Porter-branded financial-planning magazine, sold its fiction titles (at that point, the sf magazines Analog and Asimov's along with the two crime-fiction titles) to Dell's magazine arm in 1991; the last Anthology issues (including those spun off from the sf magazines) had appeared in 1988 (dated 1989). In 1996, Dell sold its magazine group, by then mostly devoted to crossword/word puzzle and astrology magazines along with the four fiction titles (Dell had briefly published an impressive Louis L'Amour Western Magazine as well in the mid '90s, but that had been folded before the sale and was not revived) to word-game specialist Penny Press, which has been publishing them since, doing business as Crosstown Publications/Dell Magazines. Eleanor Sullivan had been Managing Editor of Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine from 1970 at least through 1975, and was handed the reins to AHMM when it became a Davis Publication till 1981's penultimate issue; in 1981, after the death of Frederic Dannay, she edited both monthly magazines for about a year, and then handed editorship of Hitchcock's to Cathleen Jordan, a book editor who had been recommended to Joel Davis by Isaac Asimov. Jordan was a less-sure hand at the magazine, but did publish more horror fiction than Sullivan had, so a small favor there. Sullivan also edited, as a consequence, the first ten issues/volumes of Alfred Hitchcock's Anthology magazine, and under their various titles in the Dial Press editions. AHMM, as this anthology-issue might suggest, was often among the best of crime-fiction magazines available during its run, and had certainly drawn fiction from many of the best active cf writers. EQMM had always had a bit more prestige, at least theoretically (and perhaps paid a bit more), though when Avram Davidson lampooned it in one of his fantasy stories as Quentin Queely's Mystery Museum, he wasn't alone in finding it at times a bit fusty; Manhunt and a few of its imitators in the 1950s were briefly providing even better issues, though most had folded by the turn of the '60s and Manhunt was on a severe downward slide that would continue till its folding in '68; The Saint magazine was interesting but erratic, as was the less well-funded but more consistently published Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, the only primarily hardboiled cf magazine to run from the '50s into the '80s, unless one counted the then-mostly, but not exclusively, noirish AHMM, still published today. "Come Back, Come Back" was the second in the young Donald Westlake's short series of stories about aging, literally as well as a bit figuratively heart-sick police detective Abe Levine; they were collected, with a new story to wrap them up, in a 1984 volume. Westlake wasn't a kid by the time he was writing these, but this one was published before he was thirty; you can see him grappling with big thinks at every opportunity and not self-editing the explication of every character beat, as he would in his work not too long afterward...it probably didn't hurt that Hitchcock's paid by the word, and this story could've been a tighter short story rather than the pretty good novelet that it is (apparently, Westlake notes in the Levine collection that he stopped writing the series of novelets when AHMM rejected the penultimate one--and for decades the last--for not being sufficiently criminous; Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine picked it up for publication a few years after the last AHMM entry, with Shayne a salvage market; the new story was placed with EQMM in '84, presumably just before the book's publication). Westlake's wit and incisiveness are on display...just not his usual later concision. While Kate Wilhelm, also with one of her earlier stories, "A Case of Desperation", has her paring knife firmly in hand, and the casual bullying violence of the protagonist's kidnapper is chilling to read so plainly and concisely detailed. Worse still, for Marge, the experience of being taken at gunpoint from her bank-teller job, as hostage to help him with his robbery, has too many resonances with the rest of her life. Interesting to see the protagonist of Westlake's story and the utter, resentful, careful villain of this one both spout similar notions of How Men Are Kept From Being Men, and Don't you Want a Real Man in Your Life? Defined, apparently, as a benevolent (more or less) dictator. Contrasts slightly with the default shrewish wives and turning-worm husbands of too many of the Alfred Hitchcock Presents: tv episodes. There is a bit of oddly overemphatic foreshadowing in the story's beginning, but otherwise it's about as quietly tough and emotionally complex as one might expect from Wilhelm. More to come. The whole post is in italics because the substandard Acer laptop I'm using at the moment loves to grab not just the selected text but all the text it can just as one hits the italics button, and I'd gone through and corrected for about twenty minutes early this morning when I could've been reading more stories in this collection. So I did the faster version just now. I will soon beat the Acer to shards, or perhaps sanity will prevail. For more of today's short fiction selections, please see Patti Abbott's blog |

4 comments:

In which story did Avram Davidson use Quentin Queely's Mystery Museum…jus curious? Thanks!

"Selectra Six-Ten", in THE MAGAZINE OF FANTASY AND SCIENCE FICTION, November 1970 (the anniversary issue). Also, this was the Davidson story Edward Ferman included in the 5Oth Anniversary issue set of reprints (and the subsequent book version of that issue!)...it began as an elaborate injoke between them, when Davidson had provisionally sold a story to Ferman, who returned it for revisions before purchase, so Davidson revised it and sent it back through his agent (Robert Mills?), who mistakenly understood Ferman to have rejected it and thus sent the Ferman-driven-revisions version onto Frederic Dannay at EQMM, who bought it and published it and paid three or four times as much for it.

I love this post and someday I would like to own a copy of this book.

I'm glad, Tracy...thanks! It's an attainable goal...and Sullivan did a creditable job with the series.

Post a Comment