My previous Friday Books post is a bit of an expansion of an older one, dealing as it does with a vitally important book my mother bought for me, as the most desired part of my membership quartet in the Doubleday Book Club in 1975...in reacting just now to Matt Paust's review of a book-length interview with the writer and editor Robert Silverberg, the degree to which Silverberg's books, most but not all as part of my father's household collection (and one from his step-father as a gift to me) were key in my early science-fiction reading...to wit:

My previous Friday Books post is a bit of an expansion of an older one, dealing as it does with a vitally important book my mother bought for me, as the most desired part of my membership quartet in the Doubleday Book Club in 1975...in reacting just now to Matt Paust's review of a book-length interview with the writer and editor Robert Silverberg, the degree to which Silverberg's books, most but not all as part of my father's household collection (and one from his step-father as a gift to me) were key in my early science-fiction reading...to wit: I haven't ever read his YA novel work, but...his YA-oriented anthology Voyagers in Time was among the first if not the first of my father's paperback anthologies of sf I read (along with introducing me, of course, to the work of Wilma Shore); his YA sf anthology Beyond Control the first I borrowed from a public library; his edited

volume The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, V. 1 was the most impressive of my father's SF Book Club volumes in Doubleday's book-club hardcover format I went through, Silverberg's anthology of humorous sf Infinite Jests a fascinating slightly later remaindered hardcover pickup by my father, and a paperback of the novel Hawksbill Station the first adult sf novel I read (or, at least, the first not a previous-century classic by Wells, Twain or Bellamy), a gift from my (coincidentally functionally illiterate) step-grandfather. I'm just realizing how much Silverberg was a silver thread through my early sf reading...his was also one of the first, if not the first, sf author interviews I read, in an issue of Vertex Science Fiction magazine my father had also brought home (my brother took scissors to its front cover)...as already a crime-fiction reader at the time (see the Hitchcock Presents: review), his somewhat dismissive attitude toward why young readers weren't drawn to crime fiction as much as speculative fiction didn't sit too well with me. Odd to finally put this all together this at this late hour.

volume The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, V. 1 was the most impressive of my father's SF Book Club volumes in Doubleday's book-club hardcover format I went through, Silverberg's anthology of humorous sf Infinite Jests a fascinating slightly later remaindered hardcover pickup by my father, and a paperback of the novel Hawksbill Station the first adult sf novel I read (or, at least, the first not a previous-century classic by Wells, Twain or Bellamy), a gift from my (coincidentally functionally illiterate) step-grandfather. I'm just realizing how much Silverberg was a silver thread through my early sf reading...his was also one of the first, if not the first, sf author interviews I read, in an issue of Vertex Science Fiction magazine my father had also brought home (my brother took scissors to its front cover)...as already a crime-fiction reader at the time (see the Hitchcock Presents: review), his somewhat dismissive attitude toward why young readers weren't drawn to crime fiction as much as speculative fiction didn't sit too well with me. Odd to finally put this all together this at this late hour.

And thanks to all the readers of this blog, as this has been most widely-read year of the enterprise by some distance, apparently...it received its millionth hit this year, and its busiest month so far in this December now ending, after several other record months. I hope someone's enjoying what they see.

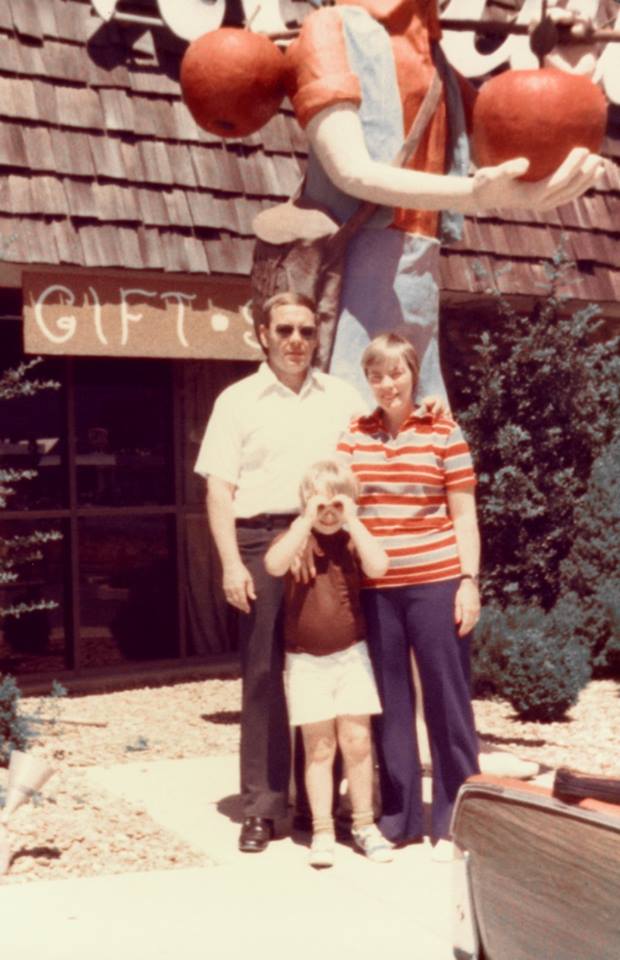

And here's a photograph of my brother and our parents, taken by me quite probably in 1977, not too long after most of the "Hitchcock" and Silverberg firsts noted above and previously, thanks to my mother, whom we lost altogether this year, and my father, like her only in a slightly different way stricken with dementia and doing his best, as she did hers, to cope with it. My brother, particularly, and sister-in-law have been doing very good work in trying to help them, as they live nearby my father's place, now. Thanks to them, and to such great friends of mine as Keiko Hassler (and her lovely family), Laura Nakatsuka, and of course, Alice Chang, There are others, also undeserved.