Vanity Fair edited by Cleveland Amory and Frederic Bradlee; picture editor: Katherine Tweed

Vanity Fair edited by Cleveland Amory and Frederic Bradlee; picture editor: Katherine TweedThe Years with Ross by James Thurber

The Book of Wit and Humor, a magazine edited by Louis Untermeyer

The Best Humor Annual V. 1-3 edited by Louis Untermeyer and Ralph Shikes

Cartoon Annual edited by Ralph Shikes et al.

Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of Comics edited and written by Dennis Kitchen and Paul Buhle

The Sincerest Form of Parody edited and annotated by John Benson

The Complete Humbug edited and originally published by Harvey Kurtzman, Will Elder, Arnold Roth, Al Jaffee and Jack Davis, with annotations and interviews conducted by John Benson and Gary Groth

Chicken Fat by Will Elder

Second HELP!-ing and Help! #23 edited by Harvey Kurtzman

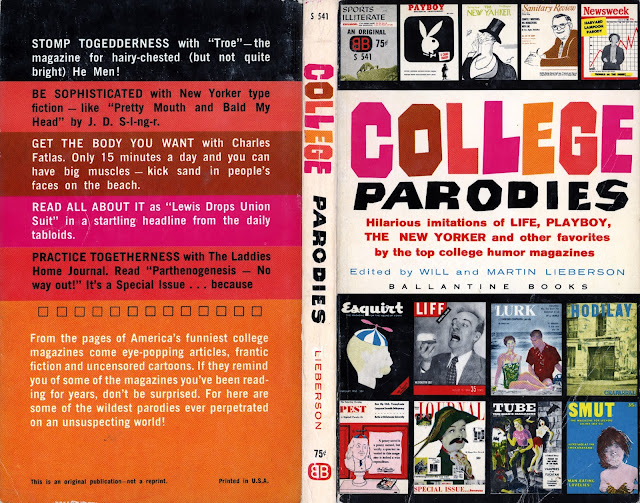

College Parodies edited by Will and Martin Lieberson (and a bit about I, Libertine by Theodore Sturgeon and Betty Ballantine)

College Parodies edited by Will and Martin Lieberson (and a bit about I, Libertine by Theodore Sturgeon and Betty Ballantine)The Realist edited and published by Paul Krassner

The Monocle Peep Show edited by Victor Navasky and Richard Lingerman

Grump! edited by Roger Price

P.S. #1, April 1966: contributions from Avram Davidson, Alfred Bester, Nat Hentoff, Gahan Wilson, Jean Shepherd, Ron Goulart, Charles Beaumont, Russell Baker, Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov, et al.; Edward Ferman, editor; Gahan Wilson, associate editor; Ron Salzberg, assistant editor

Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead written and edited by Rick Meyerowitz, et al.

Spy: The Funny Years written and edited by George Kalogerakis, Graydon Carter and Kurt Andersen

Wimmen's Comics #13, edited by Lee Binswanger and Caryn Leschen

Twisted Sisters and Twisted Sisters 2 edited by Diane Noomin

Our Dumb Century: The Onion Presents 100 Years of Headlines from America's Finest News Source edited by Scott Dikkers, Robert D. Siegel, Maria Schneider and John Krewson

Esquire's World of Humor edited by Lewis W. Gillenson

Trump: The Complete Collection (Essential Kurtzman V.2) edited by Dennis Kitchen

The Best American Comics 2015 edited by Jonathan Lethem and Bill Kartolopoulos

There have been a number of attempts at publishing humor magazines over a long-term in the United States, and for those magazines whose primary focus has been humor, it's usually been a rocky road. Magazines such as the original Life (the one Henry Luce bought the title from so as to launch his photo-journalism magazine, eventually the most popular title in his stable, in the 1930s-1960s) and Judge and College Humor (which, as the title suggests, drew on the already-established college campus humor magazines for much of its contents) all did reasonably well, as primarily but not exclusively prose magazines, in the early decades of the 20th Century. Comics magazines, whether devoted to one-panel comics such as Dell's Ballyhoo or humorous comics stories such as most of the Disney-branded comic books, among the most notable Carl Barks's work on titles devoted Scrooge McDuck and his relatives, but including a wide range of good to brilliant work by less well-remembered artist/writers or those better-known now for their eventual newspaper strips, including Walt Kelly and Jules Feiffer. Some political, some less so, some risqué (such as the long-running Sex to Sexty, though as in that example often not so sophisticated in their attempt a mixing humor and the erotic), a rare few not touching on sexual matters at all--and, certainly, such "gendered" magazines as Esquire, Cosmopolitan during and after Helen Gurley Brown, Playboy (in many ways an imitator of Esquire) and its many imitators in turn, and others (down to such much younger titles as the feminist magazines Bust and Bitch, or The Baffler) would offer humor as a large part of their remit, though even The New Yorker, or such ancestors of that magazine as The Smart Set, much less Reader's Digest of The Saturday Evening Post, were never primarily humor magazines (by intent, anyway). But we'll touch on at least two more general magazines of the 1930s (and onward) before getting back to the all-humor magazines.

So, a mix of some of my earlier writing here, and some new, about some of the humor magazines (and the collections from them) we've had over the decades...

One of the more striking covers of the first Conde Nast Vanity Fair magazine, 1914-1936.

Vanity Fair today is basically a rather pompous gossip magazine, a bit heftier (more in physical terms than the desired literary/cultural sort) than People or Us, rather better-funded and more widely sold than the New York Observer, but fitting rather comfortably into the slot between them; the greatest pity in this is how much The Atlantic today resembles it. (Late admission...the current VF has published some good journalism among a whole lot of fluff.)

The current VF is very proud of reviving the title, which had been a Conde Nast project when he still ran the company that bears his name, and which title began, after Nast bought magazine rights to a folded VF which had flourished in the 1890s, as essentially a spinoff of his big moneymaker of the time (and still), Vogue. While the new (and now old) Vanity Fair, quickly turned over to Century magazine art editor Frank Crowninshield, went from being another fashion magazine to one which was, at times frivolously or leaning into the sphere of gossip, nonetheless about culture at large in a way that the current VF has never achieved, and featuring an array of contributors that the current one would be hard-pressed to emulate.

The first issue as VF:

And the last issue (of the initial run):

And the last issue (of the initial run):

I don't have a good poachable table of contents for this anthology from the magazine, and don't have time at the moment to create one (though I think I should)(and there is a serviceable one I cop from WorldCat, below), but under Crowninshield, the magazine was able to call on, and cultivate, a remarkable number of important artists, literary and visual, as the editor was both (as Cleveland Amory is careful to note) fascinated by the new in the arts and the rest of human endeavor and very much rooted in the manners and grace of the culture he was raised in; in his first editorial (March 1914 issue), for, example, he states, with patrician charm, "We hereby announce ourselves as determined and bigoted feminists." And the humor there is only in the intentional syntax...from the first issues, he was publishing Anita Loos and Gertrude Stein, and the first major "discovery" of the magazine was a young poet and essayist named Dorothy Rothschild...who would soon be signing her work Dorothy Parker. Her first contribution collected here is "Men: A Hate Song."

The first edition, 1960:

There was no lack of male contributors, either: P. G. Wodehouse, Robert Benchley, G. K. Chesterton, Noel Coward, Louis Untermeyer are all represented in the book by works published by the end of 1920, and along with them and after, Edna St Vincent Millay, Amy Lowell, Carl Sandburg, Colette, Jean Cocteau, T. S. Eliot, Aldous Huxley, Lord Dunsany, Djuna Barnes, Clare Booth (well before her Life was making Time), Frank Sullivan, William Saroyan, Janet Flanner, Mencken and Nathan, and Kay Boyle.

1970 second edition:

And as notable as the literary contributions are the visual, both the paintings and sketches from Picasso, Matisse and Otto Khan and many others (many daringly "modern" for a mass-circulation magazine of its time; Crowninshield had been one of the major supporters of the epochal Armory Show a few years before taking on VF), and the photography...much of the portraiture collected here is among the best I've seen, with nice examples of candids and landscapes scattered...but you've never seen Texas Guinan look better (even if you've ever seen the other photos of Texas Guinan), and there are fairly iconic photos of the likes of Gloria Swanson and Greta Garbo, among other less unsurprising subjects (Ms. Guinan not being the most striking bit of photographic genius). And the book doesn't pass up the opportunity to run Covarrubias's "Impossible Interview" cartoons, in full color: Greta Garbo and Calvin Coolidge refusing to speak; John D. Rockefeller and Josef Stalin not quite getting on (though they had similar management styles).

And as notable as the literary contributions are the visual, both the paintings and sketches from Picasso, Matisse and Otto Khan and many others (many daringly "modern" for a mass-circulation magazine of its time; Crowninshield had been one of the major supporters of the epochal Armory Show a few years before taking on VF), and the photography...much of the portraiture collected here is among the best I've seen, with nice examples of candids and landscapes scattered...but you've never seen Texas Guinan look better (even if you've ever seen the other photos of Texas Guinan), and there are fairly iconic photos of the likes of Gloria Swanson and Greta Garbo, among other less unsurprising subjects (Ms. Guinan not being the most striking bit of photographic genius). And the book doesn't pass up the opportunity to run Covarrubias's "Impossible Interview" cartoons, in full color: Greta Garbo and Calvin Coolidge refusing to speak; John D. Rockefeller and Josef Stalin not quite getting on (though they had similar management styles).

Only some of the prose here is what these folks should be remembered for; The New Yorker in its early years and The Smart Set and a few others have a stronger literary legacy than that represented here, but this book is a rewarding and impressive slice through the cultural history of the magazine's time. And a sterling reprimand to the underachievement of its heir, today.

And this is the magazine that apparently encouraged W. C. Fields to note, as his potential epitaph, "I'd rather be living in Philadelphia."

from WorldCat:

Introduction. A fair kept / Cleveland Amory --

Frank Crowninshield, editor, man, and uncle / Frederic Bradlee --

In vanity fair / Frank Crowninshield --

Early memories of De Wolf Hopper / Joseph H. Choate --

Force of heredity, and nella / Anita Loos --

Sarah Bernhardt here again / Arthur Johnson --

Memory of Eleonora Duse / Arthur Symons --

Have they attacked Mary. he giggled / Gertrude Stein --

Men: a hate song / Dorothy Rothschild (Dorothy Parker) --

Modern love, by a modern French poet / Paul Geraldy --

Hall of fame 1914-1918 --

Poems / Michael Strange --

All about the income-tax / P.G. Wodehouse --

Confessions of a jail-breaker / Harry Houdini --

|

| Gloria Swanson by Edward Steichen |

Weather-vane points south / Amy Lowell --

First hundred plays are the hardest / Dorothy Parker --

Social life of the newt / Robert C. Benchley --

Hall of fame 1919 --

William Somerset Maugham / Hugh Walpole --

Soul of skylarking / G.K. Chesterton --

Poems / Edna St. Vincent Millay --

Golden age of the dandy / John Peale Bishop -

Adam and Eve / Charles Brackett --

Handy guide for music lovers / Charles N. Drake --

Man who lost himself / Giovanni Papini --

Hall of fame 1920 --

Rhyme and relativity / Louis Untermeyer --

Memoirs of court favourites / Noel Coward --

Love song / Elinor Wylie --

Picture feature: American novelists who have set art above popularity --

Ballad of Yukon Jake / Edward E. Paramore, Jr. --

Lenglen the magnificent / Grantland Rice --

Hall of fame 1921 --

Incredible jeritza / Deems Taylor --

New Hampshire again / Carl Sandburg --

Public and the artist / Jean Cocteau --

Custer's last stand / Donald Ogden Stewart --

Leavetaking (one-act play) / Ferenc Molnar --

Hall of fame 1922 --

David Garrick to John Barrymore / Stark Young --

Strange story / Elinor Wylie --

Symposium: the ten dullest authors --

Poems / T.S. Eliot --

On the approach of middle age / W. Somerset Maugham --

Hall of fame 1923 --

Fred Stone and W.C. Fields / Gilbert Seldes --

Importance of comic genius / Aldous Huxley --

Picture feature: great modern athletes --

Mrs. Fiske: an artist and a personality / Mary Cass Canfield --

Hall of fame 1924 --

One evening / Colette --

Three poems / Walter de la Mare --

Song / Helen Choate --

Memorabilia / E.E. Cummings --

Black blues / Carl van Vechten --

Big casino is little casino (three-act play) / George S. Kaufman --

Symposium: a group of artists write their own epitaphs --

Charlie Chaplin and his new film, The Gold Rush / R.E. Sherwood --

Hall of fame 1925 --

Murder of Captain White / Edmund Pearson --

Western disunion / Geoffrey Kerr --

Rudolph Valentino / Jim Tully --

Symposium: the ideal woman --

And now / Gertrude Stein (pages 280-281)

Poems of youth and age / Theodore Dreiser --

Hall of fame 1926 --

Blazing publicity / Walter Lippmann --

Picture feature: neighbors at Antibes --

Sort of defense of mothers / Heywood Broun --

Irving Thalberg / Jim Tully --

Last day / Michel Corday --

Birth of a great artist / Andre Maurois --

Theory and Lizzie Borden / Alexander Woollcott --

Hall of fame 1927 --

Three Americans / Charles G. Shaw --

Very critical gentleman / Max Beerbohm --

Outlived thing / Compton Mackenzie --

Deserted battlefields / D.H. Lawrence --

Too general public / Andre Gide --

Hall of fame 1928 --

Captain's memoirs / Alexander Woollcott --

Mental hazards of golf / Robert T. Jones, Jr. --

"God rest you merry, gentlemen ..." / Gilbert W. Gabriel --

Duel without seconds / Djuna Barnes --

This modern living / Arnold Bennett --

Hall of fame 1929 --

Art of dying / Paul Morand --

Two-time / Margaret Case Harriman --

Picture feature: child prodigies --

Mystery of Stroppingwallingshire Downs / Philip Wylie --

Tired men and business women / Geoffrey Kerr --

Hall of fame 1930 --

Picture feature: who's zoo? --

Picture feature: Raoul Dufy, painter of Paris --

Lord of the loincloth / George Slocombe --

Hall of fame 1931 --

Babe / Paul Gallico --

Ordeal by cheque / Wuther Grue --

Twilight of the inkstained gods / Alva Johnston --

Impossible interview: Rockefeller vs. Stalin / Miguel Covarrubias, John Riddell --

Impossible interview: Garbo vs. Coolidge / Miguel Covarrubias, John Riddell --

Smiles on the faces of tigers / Charles Fitzhugh Talman --

Picture feature: as a man thinketh --

Pearly beach / Lord Dunsany --

Picture feature: private lives of the great --

Lydia and the ring-doves / Kay Boyle --

Picture feature: Vanity Fair's school for actors / Joyful James / Clare Boothe --

Picture feature: on the public's beach --

Hall of fame 1932 --

How unlike we are! / Harold Nicolson --

Now there is peace / Richard Sherman --

Picture feature: my, how you have grown --

Sister Aimee: Bernhardt of the sawdust trail / Joseph H. Steele --

White poppies die / Nancy Hale --

President Roosevelt's inauguration / Miguel Covarrubias --

Dixie nocture / Frank Sullivan --

Time and a half / John Riddell --

Picture feature: American potentates (and our national pastime) --

Picture feature: history repeats --

Inflation for Ida / Frank Sullivan --

Hall of fame 1933 --

Thoughts on sin, and advertising / Frank Crowninshield --

Little Caruso / William Saroyan --

Picture feature: male and female, we create them --

Murder in Le Mans / Janet Flanner --

Picture feature: where did you come from, baby dear? --

Picture feature: actor into philanthropist --

Movies take over the stage / George Jean Nathan --

And now / Gertrude Stein --

Picture feature: even kings relax --

Picture feature: celebrities in bed --

Picture feature: hey you, mind your manners! --

Bucharest Du Barry / John Gunther --

Street / Allan Seager --

Valentine for Mr. Woollcott / Dorothy Parker --

Hall of fame 1934 --

Blunders in print / Edmund Pearson --

Time and the place / Frank Fenton --

Picture feature: Lillie in our valley --

Blind spot / John van Druten --

Bums at sunset / Thomas Wolfe --

Hall of fame 1935 --

Compensation instinct / G.B. Stern --

Mesdames Kilbourne / Allan Seager --

Omega / I.S.V.-Patcevitch.

It's also a rare example of a book in print among my entries in this series of reviews, but in discovering it was still in print (since I have the first Book-of-theMonth-Club edition from the 1950s, and first read it some twenty five years ago), I had an opportunity to read Adam Gopnick's self-congratulatory little deposit as foreward to the edition pictured above left. In noting, correctly, that Thurber's Ross seems rather a comic figure (a man who consistently affected an aw-shucks Midwestern manner while running a magazine that made a point of insulting Midwesterners on occasion, in favor of presumably un-provincial NYCers at heart if not in address; a man who constantly swore yet blanched at the notion of impropriety of any sort advocated by his ostensibly sophisticated magazine; this is not a man who lacks in comic potential), Gopnick decides that he knows Thurber was merely taking Ross down a peg, and we moderns can clearly see that Thurber was merely resentful of Ross as any writer is of their editor, and today's reader doesn't care about the details of the publishing life in the '30s...what's interesting is the relation between writer and editor, even as so cleverly distorted by grumpy old Thurber-bear. I'm not getting across the full smugness of Gopnick, but it is a pretty remarkable performance, rather amazingly echoing the sins Gopnick ascribes to Thurber only the younger man commits them less deftly. And, yes, this 21st century reader is indeed interested in the details of publishing in the 1930s, which is why I read books about publishing in the 1930s. Goodness.

But Gopnick isn't completely wrong...Thurber clearly was letting festering irritation out in much of what he wrote about Ross, but unless Thurber made up incidents out of whole cloth, one can see why he might be harboring those resentments, given the capriciousness of much of Ross's decision-making...in the manner of many great yet not consistently correct editors...who were Right even when not correct, by dint of their passion and willingness to shape their medium to fit their vision, as much as the vision of their contributors.

In short, a very useful book, as a look at both Thurber and Ross and how The New Yorker established itself, before becoming the relative bore it became under Shawn and the weathervaning creature it has been since Shawn. And Gopnick's little contribution, and the inclusion of some Thurber memos by the writer's heirs in this edition make it a slight more Interesting experience, it's true.

FFB: THE BEST HUMOR ANNUAL edited by Louis Untermeyer and Ralph E. Shikes (Henry Holt, 3 Volumes, 1950-1952); THE BOOK OF WIT AND HUMOR V. 1 edited by Louis Untermeyer (Mercury Press 1953); CARTOON ANNUAL edited by Ralph E. Shikes (Ace 1953)

Louis Untermeyer and Ralph Shikes were among the more public intellectuals in the U.S. at the turn of the 1950s, particularly the former, who was a founding panelist on the television series What's My Line? (starting in 1950). They shared a love of humorous writing and art generally, and published in 1950 the first of what would eventually be a three-volume series of Best Humor annuals, the first Best Humor 1949/50 and the next two The Best Humor Annual (without years tagged on the cover, they were published, unsurprisingly, in 1951 and '52). By 1952, Untermeyer's life was beginning to unravel in a big way, as a victim of Red-baiting of the era...he had apparently written too much for The New Masses in the 1930s (as he had for the more broadly socialist/radical The Masses earlier), before moving on to found his own magazine The Seven Lively Arts, and later signed a few too many petitions circulated by Leninist fronts and/or Leninist-supported groups for the liking of J. Edgar Hoover's FBI and

the House Un-American Activities Committee and similar agencies. He was hounded off the series and tv generally by March, 1951...leading to depression and agoraphobia, but the editors still managed to get the third volume of the annual out; probably as a consequence of the "scandal" of his sympathies, the 1952 volume was the last to be published. In 1953, both men went onto new, similar projects, Untermeyer editing a single issue of The Book of Wit and Humor for Mercury Press, which had recently sold The American Mercury to another publisher (where it, as edited by William Bradford Huie, became even more the post-war voice of the Conservative Movement in the US), but continued to publish Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and a few other titles, including the Mercury Mystery line of novels in digest-sized format...that periodical series, and the similar Bestseller Mystery, would become full-fledged magazines after the sale of EQMM in the late 1950s. Shikes kept his hand in with the first volume of Cartoon Annual, for Ace Books; subsequent second and third volumes were eventually published as edited by "Brant House" (a hardy Ace house pseudonym, even house brand, possibly employed in this case by Donald A. Wollheim). While both men would go on to notable further publication, and Untermeyer at least one more humor anthology, these were a little burst of industry in this field that apparently was both pioneering and cut short by blacklisting as much as anything else.

From the first volume, the Holt annual was meant to be a big-tent affair, featuring a wide range of approaches from satire to mildly amusing upbeat stories that were a bit more elaborate than the collections of anecdotes and jokes Bennett Cerf, Untermeyer's essential successor on What's My Line?, was prone to assemble (often without crediting his sources). Most of the most famous humorists of the period were represented in the three volumes, even if the number of cartoons in those volumes was rather restricted; Kirkus Reviews noted about the 1950 entry, "In full and in part, here are poetry, articles, fiction, cartoons, whose authorship ranges from Cleveland Amory, Robert Benchley, Bob Considine, Wolcott Gibbs, the Gilbreths, Langston Hughes, John Lardner, David McCord, Ruth McKenney, Ogden Nash, [S. J.] Perelman, [Robert] Ruark, on to Louis Zara and Maurice Zolotow." Only the editors didn't slight women contributors quite as much as Virginia Kirkus or her staff did here, and such up and comers as Ray Bradbury are also included. The conceit of arranging the contributions alphabetically by author was abandoned after the first book.

With the discontinuation of the Holt annual, and Untermeyer's passage through his period of (understandably mildly paranoid) depression, Lawrence Spivak at Mercury Press, already the moderator of NBC-TV's Meet the Press at this point, presumably felt safe enough to release the one issue of the prospective magazine The Book of Wit and Humor, which while less time-bound than the previous annual was similar in content and diversity, featuring many short bits and unlike the other Mercury Press magazines essentially no original material in the issue aside from editorial introductions and the weak exception of a joke column or two. Meanwhile, perhaps sundered in the face of anti-Untermeyer Activities (and his houseboundedness), Shikes moved onto the first annual multi-source collection of cartoons I'm aware of, drawn from the same sort of magazine and newspaper sources (Saturday Evening Postto The New Yorker to the New York Herald-Tribune) they had tapped for the Holt annual; perhaps the notoriously low royalty rates at Ace dissuaded Shikes from continuing, even though Ace did...one doubts that Ace was his first choice of publisher.

Indices for these titles to come...the 1949/50 volume just arrived yesterday, and I haven't had the opportunity to get to a scanner for a cover image; the blue volume is the 1951 volume, the red and black the 1952.

Indices for these titles to come...the 1949/50 volume just arrived yesterday, and I haven't had the opportunity to get to a scanner for a cover image; the blue volume is the 1951 volume, the red and black the 1952.

For more of today's books, please see Patti Abbott's blog. I believe I'll be collecting the links next week, as Patti takes the family holidays seriously.

With the discontinuation of the Holt annual, and Untermeyer's passage through his period of (understandably mildly paranoid) depression, Lawrence Spivak at Mercury Press, already the moderator of NBC-TV's Meet the Press at this point, presumably felt safe enough to release the one issue of the prospective magazine The Book of Wit and Humor, which while less time-bound than the previous annual was similar in content and diversity, featuring many short bits and unlike the other Mercury Press magazines essentially no original material in the issue aside from editorial introductions and the weak exception of a joke column or two. Meanwhile, perhaps sundered in the face of anti-Untermeyer Activities (and his houseboundedness), Shikes moved onto the first annual multi-source collection of cartoons I'm aware of, drawn from the same sort of magazine and newspaper sources (Saturday Evening Postto The New Yorker to the New York Herald-Tribune) they had tapped for the Holt annual; perhaps the notoriously low royalty rates at Ace dissuaded Shikes from continuing, even though Ace did...one doubts that Ace was his first choice of publisher.

Indices for these titles to come...the 1949/50 volume just arrived yesterday, and I haven't had the opportunity to get to a scanner for a cover image; the blue volume is the 1951 volume, the red and black the 1952.

Indices for these titles to come...the 1949/50 volume just arrived yesterday, and I haven't had the opportunity to get to a scanner for a cover image; the blue volume is the 1951 volume, the red and black the 1952.For more of today's books, please see Patti Abbott's blog. I believe I'll be collecting the links next week, as Patti takes the family holidays seriously.

The "Brant House" volumes:

Kurtzman already had a fan in Hugh Hefner, who offered an opportunity to do a fully-slick, full-color, more "adult" humor magazine, and a few more artists, such as Arnold Roth, signed on along with a core of his staff from Mad for the two issues produced of Trump. Then a credit-line crunch, partly in the aftermath of the American News Company magazine-distributor dismemberment, slapped around the Playboy Enterprises cashflow and Hefner was, essentially, forced to fold Trump despite excellent sales; a core group of Kurtzman and his ex-Mad and -Trump cronies banded together to produce Humbug!, an inexpensive (from the distributors' point of view, probably Too inexpensive) small-format comic, which lasted for about a year and a half, from '57-'58; Kurtzman and his collaborators scrambled pretty hard for the next year or so, but received interesting assignments from such slick magazines as Playboy, Esquire, and Pageant, and Kurtzman published with Ballantine an all-original paperback comics collection, Harvey Kurtzman's Jungle Book (1958). In 1960, Kurtzman's fourth and last satire magazine emerged; James Warren, doing well with Famous Monsters of Filmland and its stablemates, was willing to partner on the release of Help! magazine, again in large-sized format but, if anything, on as much a shoestring budget as Humbug! had been. But Help! was about as important a snag in pop-culture history as Kurztman's Mad had been, reuniting most of the old crew from the previous three magazines, at least for occasional contributions, and adding such folks as Robert Sheckley, Ray Bradbury, Gahan Wilson, Serling and Algis Budrys mostly as script/text contributors, along with occasional work in this wise by the likes of Orson Bean, who also, like such up-and-coming comics and actors as Woody Allen and John Cleese (the latter in New York with an Oxbridge Fringe-inspired troupe), would star in the photos used in "fumetti" strips--similar to comic strips, with speech balloons coming from the actors in the photos. Also, for the first year of the magazine, rather more famous comedians and actors, ranging from Ernie Kovacs to Mort Sahl to Tom Poston, posed for humorous cover photos; most of these folks were apparently convinced to do so by assistant editor Gloria Steinem, just beginning her magazine-production career. She left after the first year, but was soon replaced by a promising young Midwestern cartoonist, Terry Gilliam, who was in place when Cleese was employed for his photo shoot; this would result in their mutual participation in Monty Python's Flying Circus when Gilliam moved to England to avoid the Draft in the latter '60s. Other Kurtzman-inspired young cartoonists, including Robert Crumb and Gilbert Shelton, contributed to the magazine in various ways; Crumb even a had a bit-role in a fumetti, as well as debuting Fritz the Cat in Help!. But the constant budget restrictions Warren offered, as well as his caving in quickly to the again-outraged Archie Comics folks after Kurtzman's recurring character Goodman Beaver had an adventure which thoroughly mocked Archie and company again, led to discontent...and the magazine folded in 1965. Beaver, a somewhat Candide-like figure (with an ambiguously provocative name) was pitched to Playboy, which countered with a desire to have Beaver become a female character, and the strips to have a fair amount of cheesecake in them, and thus was born Little Annie Fanny, who would be a prime source of income for Kurtzman and his usual partner on the strip Will Elder for nearly three decades. Other activities came and went, but Annie went on forever (and oddly rather resembles actress Loni Anderson, not on the scene in the early '60s, but who might've patterned her look after the character a bit).

But Kurtzman also had opportunities to teach, and see his work influence further generations of comics and comix artists, who understandably lionized him; his early projects in graphic novels were mostly stymied, aside from the collection of Goodman Beaver from Macfadden and the Ballantine original book, and best-ofs his magazines with Ballantine (Mad comics, Humbug!) and Fawcett Gold Medal (Help!). Kitchen and Buhle note that the kind of graphic novel he wanted to do, and did manage, in relatively short form, to see one impressive example published, reprinted here in color from The Saturday Evening Post, wouldn't be too common until after Will Eisner's A Contract with God appeared in 1978, and not popular nor critically acclaimed till the likes of Art Spiegelman's Maus in the next decade--true unless you take into account such works as Walt Kelly and Jules Feiffer were publishing in the 1950s and later. But it's a very handsome book and does some innovative presentations of unpublished and work-in-progress from Kurtzman and his collaborators. You would do well to supplement it as a history with such items as the Fantagraphics complete reprint of Humbug! (and its accompanying interviews) and their collection of interviews with Kurtzman, reprinted from their critical magazine The Comics Journal, but this is a valuable book. Even if Harry Shearer's witty, bitter intro is too short to be so prominently advertised.

John Benson, in his historical essay accompanying the selections from the comic books that arose, imitatively, in the wake of the sudden success of Mad in 1953-54, notes that as a passionate young fan of Mad who couldn't get enough of Harvey Kurtzman's innovative satirical comic, he would scour the drugstores and other newsstands in shops up and down Haddon Avenue, a mile or so away as I write this, from Cherry Hill to Camden, New Jersey, hoping to get a Methadone-style sustaining fix from the issues of mayfly imitators he could pick up (comics publishing has always been irregular at best, with unreliable schedules augmented, if that's the word, by genuinely awful newsstand distribution at least until the advent of the direct-sales stores). (That probably makes Benson old enough to have the kind of eyesight that doesn't appreciate the kind of microtype in which Fantagraphics chose to print his essay, and particularly his footnotes, and Jay Lynch's introduction; I certainly don't, at some decades younger.) The comic stories and one-panel/page images reprinted here are a mildly representative survey of the various titles in standard comics format, with at least one example from the publications of nine different publishing entities, usually established comics imprints (EC itself with the Al Feldstein-edited Mad ripoff Panic, Charlton, Atlas [which would eventually become Marvel], Harvey) as well as packagers for smaller or less durable companies, and at least one startup, Mikeross, which EC essentially sued out of existence, Benson suggests for being a little too good at mocking EC at their own game. Mikeross's Get Lost! has apparently been collected in at least one other in-print anthology, so Benson mostly includes here only the rather deft parody of an EC Feldstein horror comic that, along with aping the cover format of Mad and Panic rather closely and being handled and partially bankrolled by EC's distributor, might've brought EC's particularly focused wrath upon them. The other fake Mads didn't usually manage to arise to the level of Get Lost!'s sample story, though Al Feldstein's lampoon of Mike Hammer for Panic is another highlight of the book (among the supplementary images collected here is Marie Severin's sketch of Feldstein poring through I, the Jury before writing his script).

And, of course, Panic as an EC title has been (at times lavishly) anthologized in a way that Bughouse and Flip!(probably Benson's least- and most-favored imitators, respectively) have not been. And the reproduction here, including of some battered covers (presumably from Benson's childhood collection, though that isn't made clear) as well as pristine page-layouts, is excellent; my colleague and comics fan Jeff Cantwell notes that he's always gratified when no attempt is made to saturate the colors of "Golden-" and "Silver-Age" beyond those of the original images as presented. (The pages of the book do, however, have a slightly odd scent, perhaps in large part because of the kind of ink used, rather than the heavy and perhaps acid-free paper.) And while Benson is careful to mention the relatively few 8.5 x 11" magazines that immediately followed Mad's conversion away from the standard comics format (and a few latter-day imitators such as Marvel's Crazy, launched at the height of Mad magazine's 1970s success and as a part of a line of Marvel "oversized" comics), Benson doesn't note the college humor magazines that were already fellow-travelers of Mad comics in the '50s and earlier, nor such latter-day standard-comics-format titles as DC's Plop! and Marvel's Not Brand Echh; Benson is careful to note, however, that even as at EC, often the satire titles were the mutant cousins of the horror comics (as Plop! certainly was in the 1970s). And as Roger Price noted about the not quite Onlie Begetter of all this ferment at the time, you could always use this book to quiet the hum of one's potrzebie.

Humbug was the 1957-58 magazine published by a quintet of parody-comics veterans...Harvey Kurtzman had been the founding editor of Mad the comic book, and had edited the first few issues of the larger-format Mad, the new format adopted after the Comics Code had been created by the larger publishers (except for Dell and EC itself) in the comics industry to keep governmental censorship from going any further than it had in the wake of the hysteria encouraged by Fredric Wertham's "exposé" Seduction of the Innocent. Will Elder, Al Jaffee and Jack Davis had worked with Kurtzman at Mad, and continued to work with Kurtzman when he moved on to a brief career with the well-funded, Hugh Hefner-published slick magazine Trump (decades before a certain eventual presidential candidate had even been mocked as a "short-fingered vulgarian" by the not quite as shortlived slick satire magazine Spy)...Arnold Roth, already doing jazz record sleeve illustration as well as magazine comics and art, joined with the crew at that second magazine. So, when Hefner pulled the plug on Trump after the second issue, the five decided to pool their money and produce a small-format magazine, slightly larger than a standard comic book but

not much, and priced at 15c an issue rather than the standard comic price of a dime and the rather typical quarter for a full-sized magazine. Under pressure to get the magazine out on a regular monthly basis (endless improvement noodling on Kurtzman's part, among others', had helped doom Trump) in part because their partner in Humbugwas Charlton, at the height of its mobbed-up days...Charlton printed and distributed (as CDC) the magazine, and might consider kneecapping anyone who didn't have their paid-for product ready for their trucks to carry. The eleven issues they managed to produce before folding (atop all else, the odd format of all but the last, 8.5 x 11" issues, helped cause the magazine to be lost on newsstands, as it wouldn't quite stand out among comics nor certainly among most magazines of larger size) were notable, not least to the artists who put it together and those who, such as Ed Fisher and Larry Siegel and R. O. Blechman, also contributed, for the

|

| the 7th issue |

While the next item also harkens to my early love of comics, particularly Harvey Kurtzman's Mad, inasmuch as it's a collection of sketches and finished work exploring the processes of Kurtzman's long-term partner (on the Playboy cartoon strip "Little Annie Fanny"), Will Elder. Chicken Fat touches on nearly all Elder's work, from the early art school studies through his solo cartoon work (including his failed pitch for a continuing one-panel in the Charles Addams or "Family Circus" mode, "Adverse Anthony"), including caricature for newsmagazines and ad campaigns, even as a rather small book. Among the more amusing oddities included are the roughs and finished work of illustration for a parody that Playboy published 1960, "Girls for the Slime God," which Cele Goldsmith at Amazing: Fact and Science Fiction commissioned Isaac Asimov to respond to, published in the magazine as "Playboy and the Slime God" and reprinted in his collections as "What Is This Thing Called Love?"--the William Knoles parody article, the mildly salacious Henry Kuttner pulp stories that had been excerpted in the November 1960 Playboy from the brief 1930s experiment in sexed-up sf pulp, Marvel Tales, and various explications were much later anthologized by Mike Resnick, with new analysis by Barry Malzberg and others, under the Knoles title (another FFB, if ever there was).

Ballantine Books was always ready to be an innovative publisher, in the years that Betty and Ian Ballantine were in charge...sometimes the execution was less impressive than the inspiration, but they had smashing successes with publishing collections of the first years of Mad comics, while Harvey Kurtzman was still editing and mostly writing the title, and such famous comic hoaxes as I, Libertine by "Frederick R. Ewing" (where Theodore Sturgeon and Betty Ballantine wrote a novel in a marathon session, to quickly publish after New York City-based radio host/storyteller/comedian Jean Shepard asked his listeners to go ask booksellers for a nonexistent book, to see if they could get a nonexistent joke onto then as now corruptly assembled "bestseller" lists; Shepard and Sturgeon did a first edition signing in a drugstore). So, it was only natural that other such projects should arise, such as Harvey Kurtzman's

Jungle Book...and this volume, collecting mostly magazine parodies from the college humor magazines that had preceded Mad into existence, and in fact had already been gleaned for a 1920s newsstand magazine, College Humor, a spiritual though not direct ancestor of the current website of that name. Although The Onion began as a UW Madison-based publication, the Harvard Lampoon has been probably the (otherwise) most famous and the most durable of these campus magazines in the U.S., as well as the direct inspiration for the National Lampoon in the 1970s, which has left a legacy at least as large as that of its parent, which survives it (and Harvard staffers have certainly gone onto post-collegiate comedy careers in an old-grads-club, usually old-boys' sort of way, particularly on the writing and production staff of various television series; a slightly amusing prefiguring of future interaction occurred at Harvard when future NBC television CEO Jeff Zucker, as head of the campus paper the Harvard Crimson, had

|

| A 1973 collection/special issue from HL |

A certain lack of brilliance also afflicts College Parodies, as fitfully amusing as it is (and was even when I first read it as a young teen and Mad enthusiast), and as interesting as a curio of its era (it mostly reprints 1950s items from the various campus magazines, with perhaps a few earlier parody bits); it's a sort of fun to see what's mocked (complacency, manfulness, "corn") and what isn't (homophobia certainly rules OK) in the assembled humorous critiques of mass-market culture (from a period when the magazines parodied were somewhat more central to the popular culture than they are today, even if the websites that are their heirs or even sometimes their direct legacy are somewhat similar in influence now). Some of it remains on-target, at least for me..."Normal Wellwell" and the Charles Atlas ads fairly begged for the treatment they receive...even when it could've been better. But often these were early, even the first attempts to make some of these points this way, or nearly this well...definitely a book to look at if this kind of thing holds interest for one as a student of our popular culture, rather than a book to seek out as a Laff Riot, and not worth pursuing if expensive.

|

| The Panther Books (UK) paperback |

|

| Contribution from the Fitzgeralds...CH did have to Keep Up with The Smart Set and the original Life, the humor magazine, after all... |

|

| Frank Kelly Freas's cover for the Ballantine paperback, annotated. Courtesy FlickLives.com |

The late 1950s and early '60s saw a small flurry of satirical magazines, in the wake of the early/mid 1950s boomlet of satirical comics, in both standard comic-book format and, later, in roughly 8.5 x 11" magazine format, in imitation of Mad, founded by Harvey Kurtzman at EC Comics. After the establishment of comics industry self-policing after the popular embrace of Fredric Wertham's Seduction of the Innocent and similar attempts to blame juvenile deliquency on comics (among other "perverting" factors in popular culture), EC decided to publish Mad in the more adult-oriented format, and Kurtzman, for various reasons, demanded a percentage of ownership in the new version that EC's William Gaines was unwilling to offer. So, Kurtzman walked, and went on to eventually three other magazine projects, Trump (published by Hugh Hefner, and cut short by a financial crunch at Playboy Enterprises), Humbug! (published by Kurtzman and some associates themselves, and undercapitalized), and (after a 1959 collection, Harvey Kurtzman's Jungle Book, of original work for Ballantine), beginning in 1960, Help!, as a project at James Warren's publishing house, which at the time was best-known for Forrest J Ackerman's Famous Monsters of Filmland, and was getting into the large-sized comics business with such titles as Creepy and Eerie, which would eventually be joined by Vampirella. Warren was never a publisher to spend any more money than he had to, and Help! reflected its small budget (and, after an initial year of nearly monthly publication, became essentially a quarterly for the rest of its run, to the end of 1965) and some of the lack of certainty of exactly whom its audience was that had been more easily ignored at Kurtzman's previous projects. There was a sexual undertone to much of the humor, particularly in the photographic comics-style "fumetti" stories, and bits of discreet nudity, that was mostly absent from Mad, certainly, but still a certain tendency to go for the rather easy, and sometimes the rather kidsy, joke. But, despite those limitations, Help! was a locus of some rather remarkable talent, in both magazine publication and the broader world of comics and comedy; Kurtzman's first editorial assistant was Gloria Steinem, who apparently was particularly adept at talking well-known comedians and comic actors into posing for the magazine's covers, and occasionally getting them to work as fumetti actors/models (including Orson Bean, Jean Shepherd, and Jack Carter, though usually less well-known comics were employed in the photoplays...such as Woody Allen, or a visiting Briton, then in the US with a small Oxbridge Fringe-style troupe trying their luck with NYC audiences, John Cleese...by the time Cleese's strip appeared in the magazine, Steinem had moved on and was replaced as primary assistant by a young Minneapolis cartoonist, Terry Gilliam, who worked with Cleese on that shoot...and both would later work together in London on Monty Python's Flying Circus). Meanwhile, writers such as Peter De Vries, Roger Price, Algis Budrys, Robert Sheckley, Ray Bradbury, Rod Serling, Stan Freberg, Joan Rivers and (primarily a book editor) Bernard Shir-Cliff were contributing text pieces and fumetti scripts to the magazine (alongside reprinted work of Saki and Ambrose Bierce), veteran cartoonists such as Jack Davis, Paul Coker (among many of Kurtzman's associates at Mad and later), Edward Gorey, Gahan Wilson and Shel Silverstein were contributing panels and strips, and younger cartoonists also making their names in "underground" comics were contributing, such as Gilbert Shelton and his superhero-parody "Wonder Warthog" stories, R. Crumb, Jay Lynch, and others; Sid and Marty Krofft, the psychedelic puppeteers, had a piece in one issue.

So, such collections as Second Help!-ing, or the 23rd issue of the magazine (only three issues before the last), could individually seem a bit thin, but there are always solid and memorable bits, and both the evidence of what the assembled were capable of, and the since-fulfilled promise of many of the new faces on display (even if such come-ons as Jerry Lewis's tiresome piece leading off the Fawcett Gold Medal collection, or Alan Seus, of all emerging one-note performers, engaging in a weak cover-gag on the issue, were indicative of what was least about the project).

Monocle, for its part, had the most common sort of roots among US satiric magazines: it began as a late 1950s campus project, among some law students at Yale, including the co-editor of the volume cited above, Victor Navasky (who went on to serve as editor and then also publisher for The Nation magazine over most of the last four decades). The students took their cue from Mort Sahl and other emerging satirical comedians, and then Paul Krassner's The Realist, and eventually began publishing in earnest a rather well-written and well-designed irregularly issued magazine, in the sort of tall, thin format favored till recently by Foreign Affairs magazine (or am I thinking of Foreign Policy?) Boasting of contributions by regulars such as Calvin Trillin, Marvin Kitman (put up as a Republican Party presidential contender, against Goldwater in the primaries, by the magazine), fiction writer C.D.B. Bryan, and co-editor Richard Lingerman, the contributions

Monocle, for its part, had the most common sort of roots among US satiric magazines: it began as a late 1950s campus project, among some law students at Yale, including the co-editor of the volume cited above, Victor Navasky (who went on to serve as editor and then also publisher for The Nation magazine over most of the last four decades). The students took their cue from Mort Sahl and other emerging satirical comedians, and then Paul Krassner's The Realist, and eventually began publishing in earnest a rather well-written and well-designed irregularly issued magazine, in the sort of tall, thin format favored till recently by Foreign Affairs magazine (or am I thinking of Foreign Policy?) Boasting of contributions by regulars such as Calvin Trillin, Marvin Kitman (put up as a Republican Party presidential contender, against Goldwater in the primaries, by the magazine), fiction writer C.D.B. Bryan, and co-editor Richard Lingerman, the contributions

can feel a bit notional at this remove, literary Second City scenes that don't quite hit their targets as hard as might've been hoped...but such pieces as Godfrey Cambridge's "My Taxi Problem and Ours" (simultaneously dealing, early on, with the difficulties of even a well-off black man hailing a cab in NYC, and mocking the title and format of a certain clangorous, and racist, Norman Podhoretz essay of some months before), or Katherine Perlo's poem "The Triumphant Defeat of Jordan Stone", hold up pretty well...as do various other bits here and there, including challenging one-liners (under the heading, "We're Not Prejudiced, But...", "Would you want your brother to have lunch with James Baldwin?") and Robert Grossman's superhero satire strip "Captain Melanin". This Monocle should definitely not be confused with the current newsstand magazine founded in 2007. It should be noted that this "Bantam Extra" book was published in typical mass-market paperback format, and on better-than-average paper, for what was in 1965 a ridiculous price of $1, ensuring some sales-suppression...perhaps Bantam thought they had caviar for the millions, here.

And since I'm running very late with this entry, I'll simply note that the online archive of The Realist, which I've recommended before, remains available and invaluable, and much of this material remains as challenging and sadly too often pertinent as when it was published, beginning in 1958... The [then] most recent episode of Mark Maron's podcast, WTF, is an interview with Paul Krassner, he most sustainedly of The Realist magazine and newsletter, from 1958 to 2001 with a few years off for odd behavior. Maron is seeking large answers to large questions about what the ultimate meaning of Krassner's and Lenny Bruce's work is, and the nature of their challenge to society in particularly the 1960s (though of course both began their key work in the latter '50s)...which is as good an opportunity as any to drop in a plug for The Realist archive website, a comprehensive facsimile of the magazine's run. I only wished this hadn't gone up just after I'd blown my deadline for a long essay on The Realist for a collection of cult-magazine historical essays.

Roger Price briefly threw his purse into the ring, in publishing his humor tabloid Grump...which I still hope to obtain copies of and read. The contributors are somewhat unsurprising, but also make a nice counterpart to the (theoretically) somewhat more rosy views of the contributors to the even shorter-lived P. S. magazine, devoted to nostalgia, humor and personal essays.

Please see a fine entry on Grump here.

This is a magazine I've been looking for copies of (in a casual way) for about 35 years, maybe a little more. I've written about it a little previously in the blog (and received some interesting and helpful comments there), and here's the (slightly corrected) index from the FictionMags Index previously reprinted at that occasion:

P.S. [v1 #1, April 1966] ed. Edward L. Ferman (Mercury Press, 60¢, 64pp, 8" x 11") Gahan Wilson, associate editor; Ron Salzberg, assistant editor

- Details supplied by Cuyler Brooks (and augmented by me).

- 3 · Don Sturdy and the 30,000 Series Books · Avram Davidson · ar

- 12 · Would You Want Your Product to Marry a Negro · Alfred Bester · ar

- 16 · The Gentle Art of Brick Throwing · Ron Goulart · ar

- 24 · Freaks · Gahan Wilson · ar

- 32 · Child Things · Russell Baker · ar (The New York Times 1965)

- 34 · The Lost Lovely Landscapes of Luna · Isaac Asimov · ar

- 39 · Lugosi: The Compleat Bogeyman · Charles Beaumont · ar (F&SF 1956)

- 42 · When Elephants Last in the Dooryard Bloomed · Ray Bradbury · pm

- 44 · Joe Louis in Atlantic City · Jerry Tallmer · ar

- 49 · The Thirties Quiz · Robert Thomsen · qz

- 50 · Sweet and Lowdown: The Lost Jazz Years · Nat Hentoff · ar

- 58 · Captain Ahab Is Dead; Long Live Bob Dylan, Or, Are the Beatles Really the Andrews Sisters, In Drag? · Jean Shepherd · ar

- 62 · Now You See Them · Ron Salzberg · ar

Bester's essay is telling about the delights of commercial (in at least two senses) practical censorship in the period when American apartheid, at least in certain areas, was still just beginning to come undone, and the pressures newly applied by the likes of the Congress of Racial Equality from their direction to further make things Interesting for those in the advertising and commercial radio/television industries in what we can now think of as the Mad Men era. (Bester also notes that the best actor who'd auditioned to play Charlie Chan in the radio series Bester was writing in the late '40s was spiked because the actor was black, and who'd dare have a black man play a Chinese-American detective...far safer to settle on eventual star Ed Begley, Sr.). And while there is a bit of mockery of what was already being tagged Political Correctness in certain quarters in both the Davidson and particularly the Bester essays, the Shepherd is an unsurprisingly unsubtle bleat about the then-new androgyny as seen by the radio and print satirist, with particular contumely expended toward Tom Wolfe and to a lesser extent Andy Warhol; mocking the claims to the brawling life by Bob Dylan seems a bit more grounded.

Gahan Wilson's thoughtful essay about the history of the freak show (with special attention to the activities of P. T. Barnum and his associates), Isaac Asimov's survey of the end of Romantic Mars with new Mariner probe imagery and data, and particularly Charles Beaumont's memoir of his meeting with Bela Lugosi very near the end of the actor's life (and by the time of this reprint, presumably from Beaumont's film column in F&SF, Beaumont was already far gone in his fatal premature Alzheimer's), Ron Goulart's run through the history of George Harriman and Krazy Kat, and Nat Hentoff on the jazz legends of his youth are all fine, and some at least among the pioneering writing of the time about these matters. The magazine as a whole, in its first of only three issues, is more about nostalgic reflection than I expected, with the Shepherd blast (and to some extent the Bester) being the prime example(s) of the kind of pop-sociological consideration I expected to comprise more of the content, but it really is a pity on several counts that this magazine didn't flourish. It was a good start.

So, I looked at this, an example of long-term art-book publisher Abrams's newish program of moving solidly into publishing books about and collecting comics materials (a trend I applaud, as I suspect do their accountants), and it powerfully reminded me of how much I enjoyed, even when I was mildly disgusted by, the National Lampoonin the '73-'76 period when I first became aware of it and was able to gain somewhat inconsistent access to it (I was, after all, ages 8-12). My mother angrily brought me and one issue I bought back to the drugstore where I'd purchased it, for example (the same place I'd ride my banana-seat bike down to buy my "mainstream" comics, and where I'd seen my first Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and where I'd buy my father a copy of Harry Harrison's anthology Nova 4 in its Mentor Books edition for his birthday...if Mentor and Charlton Comics were mobbed up, there was a certain logic to them being easily available in my Hazardville [Hammett fans take note] neighborhood). But what strikes me as particularly interesting is how much of this book, concentrating on the consensus-best years of the magazine, is familiar to me from those years...I think Meyerowitz, perhaps intentionally, missed the comic dinosaur spread that I recall enjoying enormously. Meyerowitz makes some not necessarily popular editorial judgement (he makes a Large Point of reprinting the splash-page illustrations for John Hughes's "My Vagina" and "My Penis" while refusing to reprint the short stories themselves, which he considers jejune and trite and examples of how NatLamp went wrong in the Animal House years and later). And there's the rub, here...much of this stuff doesn't hold up well for me at all...jejune and trite and self-conscious naughtiness are all over the place, but most of the wit is simply epater Mom & Pop and Teacher. Even Mad, and Plop!, and infrequently Cracked in the same years would dig a little deeper at times, not having quite the recourse to the sexual themes and skin-magazine imagery that so angered my mother. So, this is a tribute to an era of the magazine when it was part of the wedge that would also include the Lampoon's radio series, stage shows, budding film career (and such proto-NLprojects as The Groove Tube) and, most sustainedly, Saturday Night Live. But, what it's not, particularly when compared to such other inputs of the time that I was experiencing as the Ballantine reprints of the first years of Mad then still widely in print, The Mad Reader and more, is brilliant work that will live forever, even when done by such often brilliant people as Anne Beatts, Gahan Wilson, and Tony Hendra. Oddly enough, even the aggressively self-directed "Mr. Mike" O'Donoghue often did better when someone might tell him, No, do it again and differently.

And, as satire goes, while the likes of Agatha Christie might not be credited sufficiently in some circles, Spy magazine during its heyday beginning in 1986 and lasting to the End of the Funny Years (due to takeover by new management, which failed quickly) in the early '90s, was wildly overcredited, inasmuch as most of the acknowledged models for this brainchild of magazine guy Graydon Carter and upstart writer (and latterly radio host) Kurt Andersen, such as The Smart Set or The New Yorker (in part) or Private Eye, took on rather more daunting targets for parodic criticism than Donald Trump, even if the Trumps of the time were getting entirely too much of a free ride [this all written before the Republicans and the Electoral College put our current idiotic Fearless Leader in place]. To daringly mock the nightlife habits of reasonably famous people (even if it meant glancing reference to actor Lisa Edelstein when she was still club kid Lisa E) wasn't exactly coverage of the Scopes trial nor the Official Secrets Act nor even "Backwards ran sentences till reeled the mind"; and while some of the snark (Spy didn't invent snark, but tried to buy the patent) had some import outside the kind of circles The New York Observer somewhat less ambitiously serves today [currently co-owned by Jared Kushner, currently the son-in-law of our clown-pres.] (the mockery of Never Too Rich or Too Thin was certainly on-target and more necessary in NYC than in many places, but useful everywhere), too often Spy was, even at its best, self-congratulatory and navel-gazing to a fault in the way it conducted its business, and this history (mostly by George Kalogerakis, with the editors interpolating at will) and anthology makes the faults even more than the strengths of the magazine as clear as did Rick Meyerowitz's similar Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead (which I've also written about too briefly) for National Lampoon, similarly half-assed and credited for the full delivery in the decade previous...while similar incomplete, but less overrated and less well-remembered, successes such as Help! and Monocle are too-often overlooked, to say nothing of the less overlooked but less popular, and rather more consistently on-target, The Realist. So it goes, as more than one relevant writer enjoyed noting.

So, [in 2011] having picked up such fairly recent books over the last few weeks as Jules Feiffer's memoir, Backing into Forward (Nan A. Talese/Doubleday--"a division of Random House," still seems so odd), and Lynda Barry's book of inspiration mostly for young adult writers (but for anyone, really, particularly those of us who are fans of her "Ernie Pook's Comeek"), What It Is (Drawn & Quarterly), the earlier influences also come to mind, including the two titles that really sucked me back into reading comics aimed at adults...Love and Rockets, the intertwined comics stories by Jaime, Gilbert and sometimes Mario Hernandez (and now an annual magazine), and the assembled contributors to Wimmen's Comix, not least the 13th issue, from 1988 (courtesy the Women in Comics wikia):

So, [in 2011] having picked up such fairly recent books over the last few weeks as Jules Feiffer's memoir, Backing into Forward (Nan A. Talese/Doubleday--"a division of Random House," still seems so odd), and Lynda Barry's book of inspiration mostly for young adult writers (but for anyone, really, particularly those of us who are fans of her "Ernie Pook's Comeek"), What It Is (Drawn & Quarterly), the earlier influences also come to mind, including the two titles that really sucked me back into reading comics aimed at adults...Love and Rockets, the intertwined comics stories by Jaime, Gilbert and sometimes Mario Hernandez (and now an annual magazine), and the assembled contributors to Wimmen's Comix, not least the 13th issue, from 1988 (courtesy the Women in Comics wikia):

Occult Issue

Editors: Lee Binswanger and Caryn Leschen

Cover by Krystine Kryttre

The Visit by Trina Robbins

Ladies by Carol Tyler

The Magic Lemon by Caryn Leschen

Hoodoo Voodoo by Leslie Ewing

Beyond Reason by Joey Epstein

The Night by Cécilia Capuana

Becoming Normal by Judy Becker

Clair de Lune by Rebecka Wright, Barb Rausch and Angela Bocage

Ella Gets Her Man by Pauline Murray and Suzy Varty

Futures by Angela Bocage

Emil's Cafe by Lee Binswanger

The Dead Girl by William Clark and Mary Fleener

Voodoo Woman by Carel Moiseiwitsch

While Wimmen's Comix was soon to fold (might have just folded as I was catching up with it), other similar projects arose, including one that produced some magazine issues after two popular, now ridiculously out of print anthologies:

Diane Noomin's anthologies, which of course also followed various projects of similar scope (often in magazine form) by the likes of Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chevli, and Trina Robbins, were certainly clarion calls, as well as great fun to read. (I've certainly cited the collected work of contributor Mary Fleener in FFBs past. In fact, here's a handy page from her story "The Jelly," collected in Twisted Sisters:)

And if any magazine has taken up the mantle of The Realist, and actually delivered on its promise (not without some minor missteps and easy jokes along the way), it's The Onion, alas no longer a tabloid as well as a multimedia webzine, but still very much with us...I thoroughly enjoyed their first book, and much of what else I've read, seen and heard from them. Their one branded cinematic film, however, is about as much a fizzle as Mad's similar misadventure ..and the vast majority of National Lampoon's...

...and speaking briefly of tabloids, it is more than remarkable that for a couple of years, the National Enquirer's parent company was the publisher of both their intentionally humorous/outre The Weekly World News and, through purchase of the corporation of which it was a subsidiary, Cracked, the most durable of the Mad imitators. Not long after, Cracked folded as a magazine, but was reborn as a website and multimedia concern almost as interesting as The Onion's and at least semi-serious in it critique of the world around us...The Weekly World News was folded soon after, and is mostly kept green in memory due to the traveling productions of Batboy: The Musical, from the most widely-loved character the intentionally fake "news" of the WWN tended to feature...while parent tabloid the Enquirer continued to flourish, and expended no little energy in helping, probably effectively among his voters, get Donald Trump elected, after a fashion. At least among the actual humor tabloids, we still have the pleasant if mild Funny Times...

Anthologies of humor remain a tricky thing. In 1964, Lewis W. Gillenson, former editor of Coronet and about to begin his career, in 1966 as VP and Editor-in-Chief at Grosset and Dunlap, as boss editor at a number of different publishing houses before his death in 1992, was allowed to survey the backfiles of Esquire, a magazine which had, like The New Yorker before it, established itself with the aim of at least secondarily being a home for humor and wit, while in its case being a handsome, sophisticated magazine for men. Esquire staffer David Newman was tasked with writing the chapter introductions and running commentary through the book, so that Gillenson was not required (or perhaps was not trusted) to explain why his selections were so much more redolent of Coronet than what we might've expected from a selection from Esquire...

And when you don't get David Newman, who with Benton also manage to cough up a rather remarkably fogeyish parody of Mad magazine as it was ca. 1964 , less than ingeniously titled Bad, much of the point of which being how nihilistic as well as gauche the rather restrained and bland Mad of that era was. There are single pieces each from Parker and Lardner and Thurber and Jules Feiffer and Ed Fisher and Jessica Mitford and Philip Roth and Harvey Kurtzman and David Levine and Mencken (and George Jean Nathan profiling Mencken) and Terry Southern's minor classic "Twirling at Ole Miss" ...the major intrusion of what Esquire was becoming famous for in the pages...even Newman, as original writer of the Hayes-commissioned (and apparently a Harvard Lampoon concept in the Hayes years there) "Dubious Achievement Awards" beginning in 1962, is not represented by any of those then-available pieces...and not by any means because excessively topical pieces have been eschewed. And the selection of single-panel cartoons at the back of the book is somewhat surprisingly Off, as well, most of them feeling like New Yorker rejects of the time, though Gahan Wilson's sole representative work is unsurprisingly a highlight. Gloria Steinem, from about the period she was assistant editor of Kurtzman's Help! magazine (where she was succeeded by Terry Gilliam, before it folded and he draft-dodged to England) does contribute some wit to the "service" article for university freshmen, "The Student Prince", in collaboration with Benton, who is also overrepresented.

I hope to provide an index to this one soon, as no one else online seems to have done so.

But before Kurtzman was to begin editing Help! at the penny-pinching Warren Publications, or going broke after self-funding Humbug with his fellow staffers, but not long after leaving Mad when William Gaines wouldn't allow him partial ownership of the newly reformatted magazine, he was able to produce two 1957 issues (and get started on a never-released third) of Trump, a magazine which had no relation to our current lampoon of a U.S. president. Lavishly funded by Kurtzman fan and not-quite-pro-level cartoonist Hugh Hefner (someone's joke was that Trump had an unlimited budget, but still managed to exceed it), Trump strove to be adult in ways that Mad had never quite allowed itself to be, and was the first project where Kurtzman was able to work extensively with such similar spirits as Arnold Roth (one of the partners in the immediate successor Humbug)...published on slick paper in full color, and costing a somewhat prohibitive 50c a copy, the simple freedom to do what they wanted often seemed to work against the perfectionist Kurtzman...the two issues were published several months apart, in what was meant to be a bimonthly to start. Not having the impetus to produce more work more regularly also perhaps resulted in the feeling most readers get that the magazine didn't get to shake itself down, to find a firm footing in what it was hoping to achieve, compared to the other Kurtzman magazines...but this lavishly produced facsimile volume, featuring the two issues, some of the roughs and first drafts of material from them and the prospective third issue, and commentary by project editor Dennis Kitchen and others is a handsome and valuable book...but not one, as one moves from piece to piece in the archive here, very often compellingly funny, even when achingly well-done. A brief piece from Playboy hyping the new magazine is excerpted rather than run in full, which seems odd, given the Playboy branding (perhaps meant to diffuse the damage to the Trump title by 2016); Hefner's publishing company was running into some financial pushback by the time of Trump's second issue, and perhaps Hefner was also not too pleased by sales reports, but, as everyone notes, he did donate what had been Trump's rented office space in New York to Kurtzman and company for use till the lease ran out as homebase for the slightly more durable Humbug...

While Jonathan Lethem is a frequently brilliant writer, and a lifelong enthusiast of comics (he draws as well as writes his very funny comic strip of an introduction to this tenth annual volume, having just, as he notes, published his first scripts in professional comics), he (as he might insist, himself) was perhaps the least qualified guest editor the series had up to that point, and further admits that he's been particularly unengaged with "mainstream" or large-publisher, narrative-driven, mostly superhero-featuring comics...so they, and most of the kinds of comics those publishers will also offer, including crime-fiction and horror comics, are largely missing from this volume. And while that in itself isn't crippling...there's a lot of good work done in other modes in the comics field, and most of that in more need of exposure than the large publishers' work, for the most part...the heavy reliance in this volume on excerpts from graphic novels and other longer works, and almost no complete works as presented, makes for a less satisfying experience, if, again, a set of valuable pointers. And leading off with Roz Chast and Jules Feiffer does tend to set the bar high, even for such fellow veterans as Peter Bagge.

Unlike the first two volumes above, not everything here strives at all for humor, but much of it does, and much of that succeeds...rather better than the cover image, as cute a notion as it is (Raymond Pettibon's Ignatz Mouse drawing on the back cover is rather better)...

From WorldCat:

The Best American Comics 2015

| Editor: | Jonathan Lethem |

|---|---|

| Publisher: | Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015. |

Mom and dad.

Can't we talk about something more pleasant? (excerpt) / Roz Chast ;

Kill my mother (excerpt) / Jules Feiffer

Superheroes détourned.

Theth (excerpt) / Josh Bayer ;

Sadistic comics / R. Sikoryak ; Mathilde's story / Diane Obomsawin ;

Blane throttle (excerpt) / Ben Duncan

Storytellers.

The wrenchies (excerpt) / Farel Dalrymple ;

Prometheus / Anders Nilsen ;

Palm ash / Julia Gfrörer ;

The good witch, 1947 / Megan Kelso

Voices.

No tears, no sorrow / Eleanor Davis ;

Pretty smart / Andy Burkholder ;

The Colombia diaries, Sept 14-16 (excerpt) / Gabrielle Bell

You might even hang them on your wall.

No title (I was fumbling), no title (the credits rolled), and no title (as we can) / Raymond Pettibon ;

Lâcher de chiens / Henriette Valium ;

Pythagoras / Ron Regé, Jr. ;

76 manifestations of American Destiny (exerpt) / David Sandlin ;

Cretin keep on creep'n creek / Mat Brinkman ;

briefly, before dawn / Rosaire Appel

No title (I was fumbling), no title (the credits rolled), and no title (as we can) / Raymond Pettibon ;

Lâcher de chiens / Henriette Valium ;

Pythagoras / Ron Regé, Jr. ;

76 manifestations of American Destiny (exerpt) / David Sandlin ;

Cretin keep on creep'n creek / Mat Brinkman ;

briefly, before dawn / Rosaire Appel

Biopics and historical fictions.

selections from Hip hop family tree / Ed Piskor ;

Woman rebel : the Margaret Sanger story (excerpt) / Peter Bagge ;

The Great War (excerpt) / Joe Sacco

selections from Hip hop family tree / Ed Piskor ;

Woman rebel : the Margaret Sanger story (excerpt) / Peter Bagge ;

The Great War (excerpt) / Joe Sacco

Working the cute nerve.

Fran (excerpt) / Jim Woodring ;

Little Tommy lost : book one (excerpt) / Cole Closser ;

Mimi and the wolves (excerpt) / Alabaster ;

Pockets of temporal disruptions (excerpt) from Safari honeymoon / Jesse Jacobs ;

Misliving amended / Adam Buttrick

Raging her-moans.

My year of unreasonable grief (part four) (excerpt) from Lena Finkle's magic barrel / Anya Ulinich ;

Someone please have sex with me / Gina Wynbrandt ;

After school (excerpt) from Unloveable, vol.3 / Esther Pearl Watson

The way we live now.

Informanics (exerpt) / Matthew Thurber ;

Cross delivery, Screw style, How did you get in the hole?, The pen, and We can't sleep from The hole / Noel Freibert ;

Comets comets / Blaise Larmee ;

Crime chime noir / A. Degen

Informanics (exerpt) / Matthew Thurber ;

Cross delivery, Screw style, How did you get in the hole?, The pen, and We can't sleep from The hole / Noel Freibert ;

Comets comets / Blaise Larmee ;

Crime chime noir / A. Degen

Brainworms.

No class (excerpt) from School spirits / Anya Davidson ;

Net gain, Swiping at branches, and The perfect match / Kevin Hooyman ; Behold the sexy man! from Well come / Erik Nebel.

***For more of today's books, please see Patti Abbott's blog...

Panel dedicated to Trump at the 2016 New York Comic Con. From left to right: John Lind, Denis Kitchen, Arnold Roth, Al Jaffee and moderator Bill Kartalopoulos.

For more focused citations of today's books, please see Patti Abbott's blog.

7 comments:

Lots of great stuff here. Krassner and the Realist are much in need of some attention. I didn't know about the online archive -- I need to find some favorite back issues. P.S. was an excellent magazine; I had a surge of nostalgia upon seeing the cover of #3. Of course, as a long-time listener to Jean Shepherd's free-form radio show, anything associated with him was automatically cool back then (and maybe now), including the I, Libertine hoax. Thanks for providing all of this fine stuff.

Thanks, Jim...this is mostly a redux post, cobbling some older reviews together rather too quickly, and adding a few new bits here and there...it's been an odd, busy week, alas. Glad it could serve at least two purposes!

Todd, since I have read many of these back in the day, you brought back a lot of good memories. One item that has stayed with me over the years was a brief "grump" (I can't remember from whom): urinals that splash back! -- it was in the same issue in which Asimov grumped about trash pickup in Newton, MA.

I read MAD magazine for a couple of decades, mostly 1960s and 1970s. I wish I'd kept them. After that, I read compilation volumes from time to time. Now, everything that's supposed to be funny is on YouTube.

Jerry--glad I triggered a few good memories! And thanks for that memory of GRUMP...poorly-designed urinals and suburban trashing does seem about right for the time and venue...

George--well, there is a fair amount of what's funny online these days (webzines, podcasts, and not a few multimedia sites), but by no means is everything or even any useful portion of everything restricted to YT...or even to all the video platforms. But if you're looking for animal videos, you're on...I'm surprised your collector's urge allowed you to dispense with your MADs, but I don't seem to have held onto mine (though I had two mildly catastrophic moves for some subset of my 8.5x11 inch magazines...several years of SCIENCE and the early issues of TWILIGHT ZONE at least in the first...

I have, and have read, the YEARS WITH ROSS as well as the Letters volume. A favorite, and worthy of rereading.

I thought so as well. I suspect the hostility Gopnik lavished on it was encouraged by the would-be Keepers of the Myth. People try to pretend that William Shawn's petty power-trips were endearing, after all.

Post a Comment