- SF: Authors' Choice 4

- Editor: Harry Harrison

- Date: 1974-01-00

- ISBN: 0-399-11188-3 [978-0-399-11188-4]

- Publisher: Putnam

- Price: $5.95

- Pages: 248

- Format: hc

- Type: ANTHOLOGY

- Cover: SF: Authors' Choice 4 by Paul Lehr

- Warrior • [Childe Cycle] • (1965) • short story by Gordon R. Dickson

- Bad Medicine • (1956) • short story by Robert Sheckley [originally as by Finn O'Donnevan]

- Old Hundredth • (1960) • short story by Brian W. Aldiss

- The Forgotten Enemy • (1948) • short story by Arthur C. Clarke

- The Last Flight of Dr. Ain • (1969) • short story by James Tiptree, Jr. (Alice Sheldon)

- The Man Who Loved the Faioli • (1967) • short story by Roger Zelazny

- The Autumn Land • (1971) • short story by Clifford D. Simak

- A Sense of Beauty • (1968) • short story by Robert Taylor

- But Soft, What Light ... • (1966) • short story by Carol Emshwiller

- The Fire and the Sword • (1951) • novelette by Frank M. Robinson

- The Misogynist • (1952) • short story by James E. Gunn

- Ullward's Retreat • (1958) • novelette by Jack Vance

- Et in Arcadia Ego • (1971) • short story by Thomas M. Disch

- All of Us Are Dying • (1961) • short story by George Clayton Johnson

- Fair • (1956) • short story by John Brunner [originally as by Keith Woodcott]

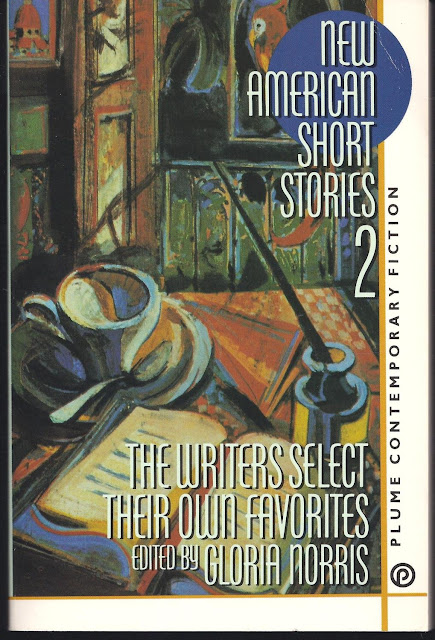

New American Short Stories 2: The Writers Select Their Own Favorites edited by Gloria Norris, Penguin/New American Library/Plume 1989

| Introduction / Gloria Norris The Pacific / Mark Helprin -- (ss) The Atlantic Monthly March 1986 Squirrelly's Grouper / Bob Shacochis -- variant form: "Fancy’s Grouper", (ss) Playboy March 1989 The Unfaithful Father / Judith Rossner -- (ss) Mademoiselle August 1986 Smorgasbord / Tobias Wolff -- (ss) Esquire September 1987 (Full Text) The Wars of Heaven / Richard Currey -- High Plains Literary Review, 1986 Temporary Shelter / Mary Gordon -- from her 1987 collection Temporary Shelter Research / Max Apple -- (ss) Harper’s Magazine #1640, January 1987 Lawns / Mona Simpson -- Iowa Review, 1984 Facing the Music / Larry Brown -- Mississippi Review, 1986 Cooker / Frederick Barthelme -- (ss) The New Yorker August 10 1987 A Lot in Common / Veronica Geng -- (hu) The New Yorker January 25 1988 Orpha Knitting / Isabel Huggan -- Western Living, 1987 The Phantom of the Movie Palace / Robert Coover -- from his 1986 collection A Night at the Movies Travel / Sue Miller -- from her 1987 collection Inventing the Abbotts and Other Stories The Curse / Andre Dubus -- (ss) Playboy January 1988 The Gift of the Prodigal / Peter Taylor -- (ss) The New Yorker June 1 1981 Be-bop, Re-bop & All Those Obligatos / Xam Wilson Cartier -- excerpted from her 1987 novel Be-bop, Re-bop Wejumpka / Rick Bass -- Chariton Review, 1988 Memphis / Bobbie Ann Mason -- (ss) The New Yorker February 22 1988 Queen for a Day / Russell Banks -- from his 1986 collection Success Stories Two anthologies, both the last in their sequences for editors Harrison and Norris, despite good reviews and an almost fool-proof concept for an anthology (or a short series of them)...get impressive authors to choose their own best, or at least for this purpose currently most favored, short fiction (a few novelettes or even a novella or two sneak into both volumes), and ask the writers to provide a headnote (Harrison's books) or an afterword (Norris's) to their story choices, which can lead to various sorts of amusement when not also enlightenment. Norris, perhaps shortsightedly, asked in both her volumes for stories published in the last three years or so that had remained favorites, making for anthologies that, for devoted fans of the writers in question (and regular readers of The New Yorker particularly), provided a litany of often familiar (and still fresh in memory) stories...Harrison, conversely, asked for overlooked stories from his contributors, which allowed them to range freely through their careers, and at times pick out something from their key developmental steps, as they were finding their way. Happily, Carol Emshwiller's 1966 story, as she describes in her headnote, takes on both her early attempts to move away from traditional plot and the increasing irritation she'd been feeling at the plethora of human-robot/AI romance stories she'd been reading, many of them ignoring the apparent warning of Lester Del Rey's early and much revered story on this subject that those who would seek out such a relation would tend to be emotionally stunted...one wonders what Emshwiller made of the technological developments already in place at the time of her death a few years ago allowing for greater ease of simulated romance and/or sex with hardware and software, if not quite up to the limited sentience of the stories (and similar narratives) in question. "But Soft, What Light..." not only posits an experimental robot and AI programmed to be a writer, but a machismic writer in the mode of Norman Mailer and his less flamboyant brethren, and its human companion, a young woman hired by the engineers and the robot's support staff in the Department of Contemplative and Exploratory Poetry to be its "vestal virgin"...and she displays all the self-deluding behaviors of the women who put up with "genius behavior" from their writing (or otherwise artistic) men, up to treasuring the knowledge that she is somehow loved by her artificial narcissist companion more than she worries about the minor and not so minor abuses she suffers, consistently excusing and praising her artificial guy. A blackly comic story, seemingly coming in part out Emshwiller's observations of too many women in the artistic communities she was a part of (with her painter and filmmaker husband and their Levittown house being a sort of Long Island bohemian locus). Emshwiller notes that she considered this story also part of her attempt to write more bluntly and honestly about sex and the relations around those interactions, and she was surprised this particular story had never been picked up for reprinting (after its first book publication here, it wouldn't be reprinted again, as far as I can tell, till Emshwiller included it in her 1990 collection The Start of the End of It All, and eventually in the first volume of her Complete Stories). She also notes that she didn't think this made her part of "the New Wave", though she enjoyed the work so tagged for the most part, since they had Agendas...not fully admitting that her agenda wasn't too far from those usually ascribed to the (admittedly somewhat amorphous) New Wave in sf. Bobbie Ann Mason's protagonist Beverly is only slightly better off with her choice of life-partner, father of their two children and now ex-husband, a man who, like Beverly, isn't too sure of what he wants but has certainly lurking dread of what he doesn't want, and has some difficulty figuring out how to actively work for the former rather than letting resentment allow him to act out abruptly and sullenly (though, at least, not violently so much as to a certain degree selfishly, something Beverly realizes she isn't immune to, either, though she tries to be less disruptive and sulking than her ex). To further complicate matters, they aren't done with each other sexually, at least not in terms of both lust and empathy, and share custody of the children...which will be made more difficult as he intends to take a job in South Carolina, quite some distance away from their current abodes in western Kentucky, not too far a drive from Memphis, TN. The story is rich in details of their lives and those of their friends and extended families, and elegantly casual references to pop music and science-fictional films and related matters. Beverly is as effortfully trying to find a reasonable life for herself and help those around her find one as well, as much as the relentlessly nameless protagonist of Emshwiller's story is trying to invest herself in the notion of her self-abnegating sacrifice being for the Greater Good for her artificial partner and the great works it's going to be capable of, Real Soon Now. Mason notes in her afterword to the story that she envisioned a catastrophic ending for Beverly in the first draft, which among other unsatisfying respects left the impression of Beverly punished for leaving her husband; the next draft ended with what she suggests is The English Department ending: "Beverly was gazing at tantalizing visions of ambiguity in the reflections of the sky in the picture window"...and in final form Mason simply had Beverly going about the business of life, including that pertaining to her ex. Emshwiller, more in farce than minimalism in her story, has the budding AI/robot poet compose: I love you. "Let me count the ways." One, two Three, four Ear neck leg Adam's apple (Five) Wrinkle under arm Big toe. That's seven But that's not all. Let one who can count, count, And in a microsecond, To thousands. Charms have never been better catalogued Than this From whorl of fingertip through pubic hair line I love you. Its later work is slightly more adept, if no less comically so. For more of this week's Short Story Wednesday entries, please see Patti Abbott's blog. |