It's a time of memorials for me, so, a slightly augmented redux post, featuring two gracious artists I've read for half a century, and had the pleasure of meeting in person on one occasion each...though had a correspondence with Barry that went on for a couple of decades.

Kit Reed, 7 June 1932-24 September 2017

Barry Malzberg, 24 July 1939-20 December 2024

Thief of Lives by Kit Reed (University of Missouri Press, November 1992, 0-8262-0850-9, $19.95, 179pp, hc, co) Can be read here.

- 1 · In the “Squalus” · Kit Reed · ss Transatlantic Review #41, Winter/Spring 1972

- 11 · Journey to the Center of the Earth · Kit Reed · ss [Village] Voice Literary Supplement

- 23 · Winter · Kit Reed · ss Winter’s Tales 15 ed. A. D. Maclean, Macmillan UK, 1969

- 32 · The Jonahs · Kit Reed · ss Tampa Review

- 45 · The Protective Pessimist · Kit Reed · ss The Texas Review

- 56 · Fourth of July · Kit Reed · ss Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture

- 67 · The Garden Club · Kit Reed · ss Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture

- 80 · Clement · Kit Reed · ss

- 93 · Queen of the Beach · Kit Reed · ss

- 104 · Thing of Snow · Kit Reed · ss Transatlantic Review #33/34, Winter 1969/1970

- 118 · Mr. Rabbit · Kit Reed · ss Transatlantic Review #51, Spring 1975

- 127 · Academic Novel · Kit Reed · ss

- 143 · Victory Dreams · Kit Reed · ss

- 153 · Prisoner of War · Kit Reed · ss Tampa Review

- 166 · Thief of Lives · Kit Reed · ss

- Winter, (ss) Winter’s Tales 15 ed. A. D. Maclean, Macmillan UK, 1969

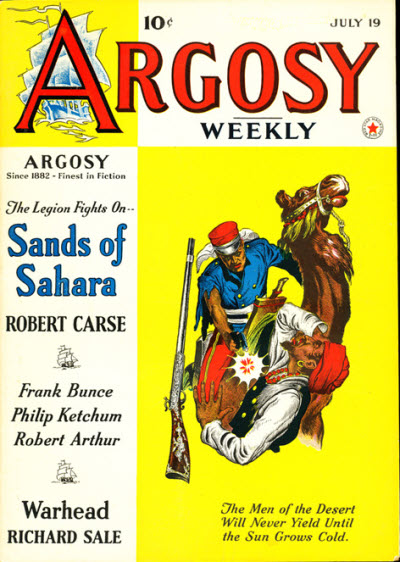

- Argosy (UK) January 1970

- The Year’s Best Horror Stories No. 1 ed. Richard Davis, Sphere, 1971

- Happy Endings ed. Damon Knight, Bobbs-Merrill, 1974

- Other Stories and…The Attack of the Giant Baby, Kit Reed, Berkley, 1981

- Murder and Mystery in Maine ed. Charles G. Waugh, Frank D. McSherry, Jr. & Martin H. Greenberg, Dembner, 1989

- Thief of Lives, Kit Reed, University of Missouri Press, 1992

- Weird Women, Wired Women, Kit Reed, University Press of New England/Wesleyan, 1998

- and, as noted (if mostly by implication!) below, in Reed's 2013 retrospective collection The Story Until Now:

Kit Reed: "Winter" (1969); Barry N. Malzberg: "Barbarians? Sure" (2020): Short Story Wednesday

Kit Reed saw "Winter" first published in the 1969 15th volume of Winter's Tales, the annual then edited by A. D. MacLean (as it would be for all its long original run, 28 annual volumes), and she included it in four of her collections over the decades, with good reason; even though it eventually becomes a suspense story, it was also reprinted in the first volume of Richard Davis's annual, with two more volumes to follow from Davis and published for some decades further in the US by DAW Books with US editors Gerald W. Page and then Karl Edward Wagner, The Year's Best Horror Stories...despite not being a horror story, per se. Grim, literate, richly-detailed character-driven stories were among Reed's favorite modes, and this story of two older sisters, living in the northern woods of the US somewhere unnamed, but the kind of country where people hunt to put up meat for the winter, and were and sometimes are dependent on what canned goods and preserves they've put aside, is a prime example of her work. Told from the point of view, and in the slightly eccentric cadences, of the older sister, one whose mild epilepsy has helped her remain something of a pariah in her community, and how she and her slightly younger and resentful sister, who has felt obligated to keep company with her sister for that reason, are like as not to argue as a matter to death and then start joking about it. One day, they find a young male stranger sleeping in their childhood playhouse, used mostly for storage, and they take him in, finding him helpful and grateful for a few day's refuge from the military basic training he's deserted...and he becomes a longer-term guest, and the source of some romantic rivalry between the two women.

The utterly realistic setting of the story, in its starkness and accommodation of lethal weather, can have an almost sfnal feel about it, abetted by the woods-folk attitudes of the sisters...but by the rather severe end to their rivalry, one has the sense of mimetic fiction doing one of the things it can do as well as historical or fantastic fiction, bring the readers into lives unlikely to be too similar to their own. And the turn toward the weirder sort of crime fiction isn't at all an abrupt change in tone.

Barry Malzberg has graciously contributed several times to this blog, and his literary jape for the 2020 annual 14th issue of The Mailer Review, a handsomely-produced little magazine published by the Norman Mailer Society out of the University of Southern Florida; my copy came as a kind gift from Deputy Editor Michael Shuman. Between them, Barry and Michael provide more nonfictional lines of set-up and afterword for "Barbarians? Sure" than the vignette proper contains, but that's more than all right, since the conceit is to give a flavor of the kind of science fiction Mailer might've written in the 1950s instead of such poorly-received work as Barbary Shore and The Deer Park. (There apparently is some surviving Mailer juvenilia of an sfnal nature, notably "The Martian Invasion".) Despite Malzberg previously suggesting that Mailer has been one of his primary influences, until seeing this vignette it hadn't quite registered how much his prose can resemble Mailer's, as the vignette proper could as easily be the work of a retooled (but not Too recalibrated) Mailer as it is of Malzberg in his more humorously baroque mode. Malzberg also slips in a sly reference to the emptiness that can be the fate of an astronaut who realizes he's more tool than heroic explorer, a theme running through some of his most famous early work (and certainly widened to encompass members of other occupations, very much including writers, as he continued to write). Shuman generously supplies an Appreciation of the vignette as postscript, explaining some of the subtler details of the pastiche and parody to the null-SF readership; I'll air the slightest of quibbles with his citation of Arthur C. Clarke and Damon Knight along with Catherine Moore as mainstays of the sf magazines Astounding Science-Fiction and Planet Stories, Clarke presumably cited as one of the best-known sf writers still, Knight as one reasonably well-known for his workshop teaching career among academics...Moore, usually in collaboration with her husband Henry Kuttner, was a key contributor to ASF, but Clarke had only a handful of stories in it (including one of his most famous, "Rescue Party"), even as Knight had a handful of stories in Planet, but none of them his major work...though ASF and PS were among the most distinct of the 1950s sf magazines, while such other good ones as Startling Stories and If would be more obviously eclectic, have a less polarized identity...Galaxy, probably the single most influential of the decade's sf magazines, also had at least as strong a slant, as did The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, edited by "Anthony Boucher" and J. Francis McComas (and magazines, particularly F&SF, more likely to have Clarke and/or Knight stories in a given issue in the '50s).

Meanwhile, from the story:

"He [the protagonist] was the first Terran in recorded history to conjoin with the Martians. It was shocking and yet somehow utterly meaningless, like the stoned and shadowy eyes of his wife who in a distant eruption of time spent, had been lying against him in the limitless field of the bed they had made and were to lie upon forever was herself an alien."

For more of this round of Short Story Wednesday reviews, please see Patti Abbott's blog.

.jpg)