Heinlein and Fast as the cover draws. John Collier's story was a reprint. Starship Soldier was, as editor/critic John Boston has noted in email, a truncated form of Starship Troopers, which was published in book form about the same time the second and final installment in the next month's F&SF was on the stands.

From the FictionMags Index and ISFDB:

- The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction [v17 #5, No. 102, November 1959] (40¢, 132pp, digest, cover by Emsh/Edmund Emshwiller) []

- 5 · The Martian Shop · Howard Fast · nv

- 25 · “From Caribou to Carry Nation” [Mad Friend] · G. C. Edmondson · ss

- 29 · Plenitude · Will Worthington · ss

- 40 · Frritt-Flacc · Jules Verne; translated by I. O. Evans · ss

translated from the French (“Frritt-Flacc”, Le Figaro Illustré, 1884/5). - 46 · I Know a Good Hand Trick · Wade Miller · ss

- 51 · Starship Soldier [Part 2 of 2] · Robert A. Heinlein · n.

- 95 · Ballad of Outer Space · Anthony Brode · pm

- 96 • Books: Without Hokum • essay by Damon Knight

- 96 • Review: The Mystery Writer's Handbook by Herbert Brean • review by Damon Knight

- 96 • Review: SF: The Year's Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy: 4th Annual Volume by Judith Merril • review by Damon Knight

- 98 • Review: A Handbook of Science Fiction and Fantasy by Donald H. Tuck • (1955) • review by Damon Knight

- 98 • Review: The Falling Torch by Algis Budrys • review by Damon Knight

- 99 • Review: The Fourth "R" by George O. Smith • review by Damon Knight

- 99 • Review: The Night of the Auk by Arch Oboler • review by Damon Knight

- 100 · Science: C for Celeritas · Isaac Asimov · cl

- 110 · Through Time and Space with Ferdinand Feghoot: XX · Grendel Briarton · vi

- 111 · The Masks · James Blish · ss

- 115 · After the Ball · John Collier · nv Lovat Dickson’s Magazine November 1933

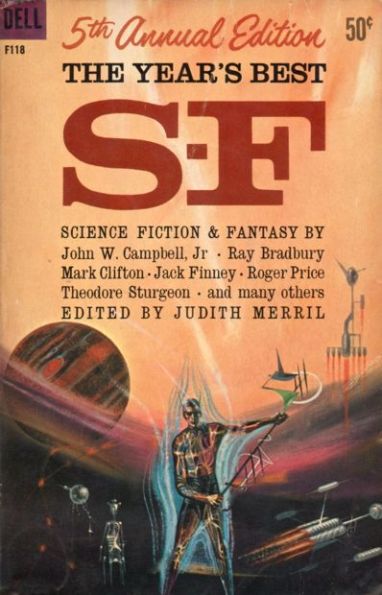

I first read the story in this volume of Judith Merril's annual:

(note the early Lawrence Block story collected below; a good volume even for Merril...)

- The 5th Annual of the Year’s Best S-F ed. Judith Merril (Simon & Schuster, September 1960, $3.95, 320pp, hardcover, anthology, cover by H. Lawrence Hoffman; paperback cover by Richard Powers)

- 7 · Introduction · Judith Merril · in

- 9 · The Handler · Damon Knight · ss Rogue August 1960

- 14 · The Other Wife · Jack Finney · ss The Saturday Evening Post January 30 1960

- 30 · No Fire Burns · Avram Davidson · ss Playboy July 1959

- 48 · No, No, Not Rogov! [Instrumentality] · Cordwainer Smith · ss If February 1959

- 67 · The Shoreline at Sunset · Ray Bradbury · ss The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction March 1959

- 78 · The Dreamsman · Gordon R. Dickson · ss Star Science Fiction No. 6 ed. Frederik Pohl, Ballantine, 1959

- 87 · Multum in Parvo · Jack Sharkey · gp The Gent December 1959

- 91 · Flowers for Algernon · Daniel Keyes · nv The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction April 1959

- 123 · “What Do You Mean…Human?” · John W. Campbell, Jr. · ed Astounding Science Fiction September 1959

- 131 · Sierra Sam · Ralph Dighton · ar The New York Times January 1960

- 134 · A Death in the House · Clifford D. Simak · nv Galaxy Magazine October 1959

- 155 · Mariana · Fritz Leiber · ss Fantastic Science Fiction Stories February 1960

- 161 · Inquiry Concerning the Curvature of the Earth’s Surface · Roger Price · ss Monocle Winter 1959 (the humor magazine)

- 163 · Day at the Beach · Carol Emshwiller · ss The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction August 1959

- 174 · Hot Argument · Randall Garrett · pm The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction February 1960

- 175 · What the Left Hand Was Doing [Brian Taggert] · Darrel T. Langart (Randall Garrett) · nv Astounding/Analog Science Fact & Fiction February 1960

- 204 · The Sound-Sweep · J. G. Ballard · nv Science Fantasy #39, February 1960

- 245 · Plenitude · Will Worthington · ss The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction November 1959

- 258 · The Man Who Lost the Sea · Theodore Sturgeon · ss The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction October 1959

- 271 · Make a Prison · Lawrence Block · ss Science Fiction Stories January 1959

- 275 · What Now, Little Man? · Mark Clifton · nv The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction December 1959

- 311 · Me · Hilbert Schenck · pm The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction August 1959

- 312 · The Year’s S-F, Summation and Honorable Mentions · Judith Merril · ms

Can't imagine why ("Snirsk!" says Ninja the cat as she walks by), but post-crisis fiction and drama is at least as common (and perhaps popular) as ever, though one of the more memorable post-crisis stories that has stuck with me through the decades (I would've read it perhaps forty years ago, and it wasn't so very new then) was by Will Mohler, who apparently published all his fiction in a five-year span from 1958-63, almost all of it signed "Will Worthington", and that was that, despite a receptive audience for it in the field.

"Plenitude" is an interesting mixture of outsider resentment of conformity culture--through that conformity seeking a kind of community and security which can be all too poisonous (hello, current crises, particularly when the current power structure is, more than usual, in the hands of particularly self-regarding irresponsible, ignorant fools), and how one might attempt to imagine a better, truer existence through turning away from all that. It's not a brilliant story, but it does rather cleverly outline what seems at first to be a post-apocalypse scenario which turns out to be something rather different, a latter-day refinement of H. G. Wells's Eloi and Morlock dynamic, if less systematically brutal. Mohler's a better polemicist than he is a fashioner of fully human characters (the adult women characters are puzzling wonders to the [not quite fully] adult viewpoint character, and this is something he brushes off improbably, given their situation...such obliviousness might make more sense in a story set in a 1960s US reasonably affluent suburb). It's a relatively short story, and it mostly surprised me back then in its critique...Mohler mockingly uses Hegelian terms to chide its upper middle-class conformist survivors, and one will find it more difficult in a quick search for the term "Parmenidean" than it should be, as our bots of today are made to be certain we must mean to search for "Pomeranian"...I believe I first read this story in the back volume of the Merril annual rather than the back issue of F&SF, which with even a glance at the contents marks it as a typically star-studded one...editor Robert Mills, like his predecessors "Anthony Boucher" and J. Francis McComas, being as much at home in crime fiction as fantastica.

I suppose I should make a study of Mohler's work in toto, as far as we know of it, with three stories in Fantastic, one each in If and the British Science Fantasy, and six in total in F&SF, the last one, along with a single story in Galaxy, as Mohler:

- * Abide with Me, (ss) Fantastic Science Fiction Stories January 1960, as by Will Worthington

- * A Desert Incident, (ss) Fantastic June 1959, as by Will Worthington

- * The Food Goes in the Top, (ss) Science Fantasy #48, 1961, as by Will Worthington

- The Unfriendly Future ed. Tom Boardman, Jr., Four Square Books, 1965, as by Will Worthington

- Decade the 1960s ed. Brian W. Aldiss & Harry Harrison, Macmillan UK, 1977, as by Will Worthington

- * In the Control Tower, (nv) Galaxy Magazine December 1963

- * The Journey of Ten Thousand Miles, (ss) The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction March 1963

- The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (UK) July 1963

- Once and Future Tales from the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction ed. Edward L. Ferman, Delphi Press, 1968

- * Package Deal, (ss) The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction July 1961, as by Will Worthington

- * Plenitude, (ss) The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction November 1959, as by Will Worthington

- The 5th Annual of the Year’s Best S-F ed. Judith Merril, Simon & Schuster, 1960, as by Will Worthington

- The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (UK) October 1960, as by Will Worthington

- SF: The Best of the Best ed. Judith Merril, Delacorte Press, 1967, as by Will Worthington

- SF: The Best of the Best, Part Two ed. Judith Merril, Mayflower, 1970, as by Will Worthington

- Hot & Cold Running Cities ed. Georgess McHargue, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1974, as by Will Worthington

- As Tomorrow Becomes Today ed. Charles W. Sullivan, Prentice-Hall, 1974, as by Will Worthington

- The Big Book of Science Fiction ed. Ann & Jeff VanderMeer, Vintage Books, 2016

- * The Swamp Road, (ss) The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction June 1960, as by Will Worthington

- * Two Whole Glorious Weeks, (ss) If December 1958, as by Will Worthington

- * The Unspirit, (ss) Fantastic August 1959, as by Will Worthington

- * We Are the Ceiling, (ss) The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction February 1960, as by Will Worthington

- * Who Dreams of Ivy, (ss) The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction November 1960, as by Will Worthington

- []Mohler, Will(iam W.) (fl. 1950s-1960s); used pseudonym Will Worthington (chron.)

***For more of today's story reviews, please see Patti Abbott's blogpost here.